How nurses don't get humour

- and why that could affect healthcare

Nurses are failing to use humour – or even recognise when their own patients are using it – even though it means they are missing vital ways to communicate, and important information about the treatment.

But exceptions can be found in medical staff tending to so-called ‘bad patients’, such as drug users, who use a brutal form of humour to bond with those often hostile to dealing with the NHS.

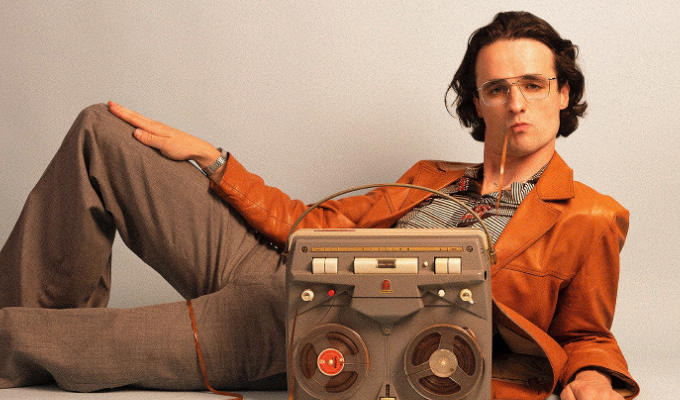

Those are the findings of a limited study conducted by health lecturer – and former stand-up comedian – May McCreddie and presented at a Centre For Comedy Studies Research seminar yesterday.

Although research has previously been conducted in the use of comedy in health care, it tends to either be about the benefits of ‘rehearsed humour’ such as stand-up or jokes – or focussing on when and why cracking gags would be inappropriate.

She also noted other research which found: ‘When doctors use self-disparaging humour they are less likely to be sued.’

Dr McCreddie investigated 12 clinical nurse specialists in fields ranging from cancer care to gynaecology, and concluded that most fail to deploy humour, even thought sharing a laugh is ‘essentially about humanity’.

In most cases, patients adopt a ‘good patient’ persona, she said, being keen to be seen as compliant, positive and independent. But this meant they presented their concerns in ‘a non threatening way’ – using subtle, self-deprecating humour.

And Dr McCreddie said that if nurses they can be alerted to this, they might be aware that something was not quite right. She cited one patient who joked that nothing had worked to ease her pain. But because the tone was modest and friendly, the nurse interpreted the sessions as ‘positive’ and ‘cheery’ – and didn’t catch on to the underlying complaints about pain.

‘We all use a different mix of humour types, but if a patient uses self-disparaging humour in isolation, or alongside gallows humour, I would strongly suggest there is a problem there that needs to be unravelled,’ she said.

Dr McCreddie, who works at the University of Stirling, added that patients were twice as likely to instigate – and reciprocate – humour than the nurses; and said this was possibly down to nurses not being confident enough to make jokes, or too keen on following rules that make no concessions for humour.

In contrast, one nurse she studied was offering female sexual health advice in tough environments such as drug drop-in centres, where patients were likely to be hostile to receiving unsolicited advice or undergoing procedures such as smear tests.

She found that this subject not only used, but initiated, ‘harsh’ humour to break the ice – joking about one addict’s seven children, quipping that ‘If I had that many kids, I’d be on speed too’.

Dr McCreddie described ‘harsh’ humour as frank and upfront, with ‘nothing subtle’ about it and using ‘violent, coarse and profane’ language. Yet such humour got results, with the nurse surveyed successfully getting information and consent from her patients.

The academic concluded: ‘The irony is that bad patients get engagement, while good patients are left wanting.’

She presented her findings at Brunel University, West London, where the Centre For Comedy Studies Research is based.

Published: 16 Jan 2014