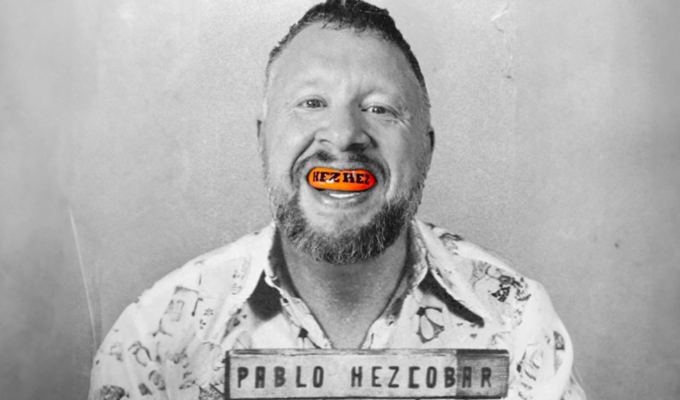

Tom Mayhew: Trash Rich

Edinburgh Fringe comedy review

Trash Rich is a slow-burning show but builds to a vital and pressing topic largely overlooked in the overwhelmingly middle-class Fringe.

Few stand-ups seriously tackle the widespread and devastating effects of poverty, Tom Mayhew argues. Comics might complain in all the artists’ bars about how the cost of their festival accommodation is going through the roof, but Mayhew is talking about people for whom the lack of money makes every day frighteningly precarious. People like him and his family. And it’s only going to get worse.

He wants to remove the stigma of talking about money in the same way comedians have become increasingly adept at blowing open the taboo of mental health. To that end, he comes clean about his own finances. Just before the pandemic ripped it all away, he considered himself a success in comedy. Half a dozen years in and with two well-thought-of Radio 4 series under his belt, he was starting to earn £1,000 a month from his chosen career and began to entertain ideas of finally moving out of his parents’ home. Well, it’s back to square one now.

The housing crisis is top of his list of concerns, with some of his relatives stuck in limbo, teetering on the verge of homelessness, even before the impending energy bills catastrophe. He paints a grim picture of life on the breadline, crowdfunding funerals and struggling for every pound under a system that squeezes the working class out of their dignity. In such circumstances, the already much-mocked advice that cutting back on crushed avocados and Netflix will help youngsters afford their own homes is patronising and pathetic.

Mayhew’s polemic is hard-hitting, illuminating and important, if often too serious to be funny. At the same time, his suggestion to ‘eat the rich’ is a long-standing satirical meme of the class struggle, stemming from the French Revolution, and he can’t really advance it. But there are light moments that do hit home, such as an analogy of society ‘ramming capitalism down our throats’ in the same way bigots complain about homosexuality. But any comic instincts are too often overwhelmed by bleak reality.

Before we get to this point, he offers accessible, authentic observational humour about working-class life, such as holidays at the Haven camps where the mascots have worrying names, flecked with an appealing streak of self-deprecation.

But when the frustrations born from the desperation of his friends and family’s desperation kick in, his passions rise, sweeping the audience up in the power of his honest, urgent rhetoric. It’s a sobering wake-up call.

Review date: 30 Aug 2022

Reviewed by: Steve Bennett

Reviewed at:

Stand 2