British lads love weakness... and I reeked of it

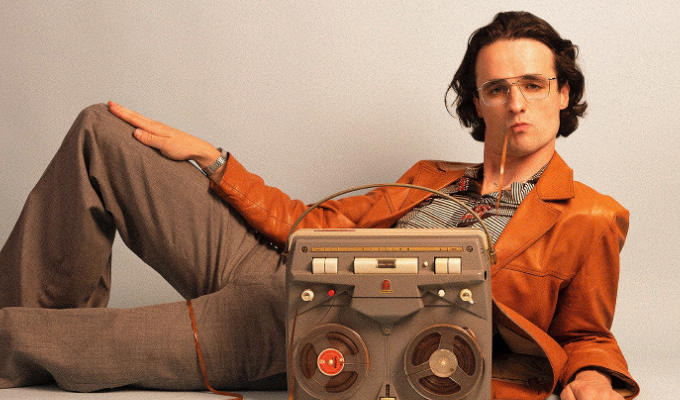

In the second extract from his memoirs, James Mullinger learns a hard lesson of stand-up

Comedian James Mullinger has written a book – Brit Happens: Or Living The Canadian Dream – about how he moved to St John, New Brunswick, and found success there after years of struggling on the UK scene. Yesterday he told how his early success on Jimmy Carr’s Comedy Idol wasn’t the breakthrough he hoped. Here he tells of another weekend of gigs, when he learned a hard lesson about overconfidence…

No one arrives at the gates of this game as the finished article. Every comic takes a beating. Every seasoned comedian’s act is an amalgam of lessons learned from the depths of failure and the heights of success.

In 2010, after five years of slogging through open spots, I finally managed to convince the Glee Club in Birmingham to give me a weekend of paid twenty-minute spots. That Friday I snuck out of the office early to catch the ninety-minute train ride into the Midlands and arrived in Birmingham tired and nervous.

All the other comedians seemed excited and full of life, vibrant and awake and fresh. They were just starting their work week, and I was at the end of mine, wiped out and stressed. I was nervous because this felt like a big moment, a rite of passage, my first paid club weekend, but I also felt depleted and was trying to shake that off.

Now, I should say that in England the clubs work differently than they do in Canada. In Canada, shows run for a hundred minutes. There is an emcee, a feature act (the opener), and a headliner. Sometimes a seven-minute open spot is inserted between the feature and the headliner. These hundred-minute shows run straight through with a table service and no intermissions.

Some clubs in North America have what they call a two-drink minimum, which means you have to guarantee you will buy two drinks at the show. No need for that in England. In England you need more of a 20-drink maximum.

Let me explain.

In English clubs there are generally four comics on a bill, plus an open spot. The open spot might do five or ten minutes, but the other acts are twenty minutes. And there is an intermission between each act because English audiences can’t be expected (read trusted) to sit more than a few minutes without a new drink in their hands. Table service would be impossible. The show would be interrupted with constant cries of "Oi, Gaz, ’ave a fuckin’ shot, mate."

So they just shut the bar between comics in the hope the audience can stay focused on the show, and then every thirty minutes they have an intermission, allowing the crowd to run to the bar and stock up on shots and pints. The way the English drink is unlike anywhere else. When the intermission is called, you literally see upwards of 200 people running, running, for the bar and buying as much lubrication as they can carry in their arms and pockets. Yes, pockets. Fingers are in pints and bottles are in pockets.

On this particular night in Birmingham, Irish comedian Martin Mor was compèring. Mor is known as one of the best in the business. He works the crowd and conjures a palpable atmosphere so all the other comics can excel at their jobs.

As he brought me up, he had been teasing a guy in the front row for being good-looking. So I walked out and picked up where Mor had left off, flirting with this guy. The audience were in fits from the first line. It was electric. A truly magical experience. And I was being paid. The dream.

I had planned my twenty minutes meticulously, or so I thought. I knew what normally took 20 minutes, but I had gone off script, and I wasn’t used to playing rooms this big or to getting such stints of extended laughter. I was only halfway through my set when I looked at my watch. I was already at 22 minutes, and I hadn’t even done half my planned material. So I was already over my time. And you never, ever over run. Or under run. Venues are very strict about this. They time you, and you take the very real risk of being banned from that venue if you don’t respect the rules.

I bounded off stage to a mass of cheering and applause. It was the best gig of my life up until that point.

Because the night had gone well, I stayed and had a couple of drinks at the club, but really I just wanted to get back to the grotty Holiday Inn to bask in the glory, to ignore all of the sirens and shouting and fighting in this bustling city centre and relive the moment in my mind over and over again.

It’s a habit of mine to take notes after shows. So I went back to the hotel and wrote, "Tonight, for the very first time in my life, I felt like a proper comedian." The sprawling, rambling entry went on to say, "After five years of doing this job, I have never felt like I could actually see myself playing an arena one day. Tonight I could."

I rose early the next day and walked around Birmingham’s city centre, and I was revelling in the thought of being a comedian, of feeling like a real, bona fide comedian. But, as always in this game, the feelings of euphoria that surround you like a warm bath can easily go down the drain. All you have to do is pull the plug.

There was a noticeable spring in my step when I arrived back at the club that night. For once I was arriving at a club the day after a set feeling like I owned the place. I was fist-bumping the bouncers. The club manager greeted me warmly. This was it. What it’s all about.

Showtime came around and, as is the case with all club weekends, the line-up was the same. Everything was the same: same time, same walk-on track, same everything, just a different 400 people jammed into the room.

Martin Mor plied his trade perfectly, spewing lines the audience believed to be made up on the spot but all very meticulously rehearsed after decades of practice. Then he introduced me.

I walked out like the cat who’d swallowed the canary. Confident. No, that’s not accurate. Overconfident.

When you take the stage at the Glee Club, you are bathed in a purplish blue light, and the audience is seated in a semicircle around you. They take up your entire field of vision, and you have your back to the wall. Except the wall behind you is actually composed of six-foot-tall, three-dimensional letters spelling out the word glee. Such a fun and chipper word. Unless you are unwittingly preparing to bomb in front of it. Then it has a rather scorching sense of irony.

I tried to replicate my opening banter from the previous night. And guess what? It fell flat.

The room descended into stillness. I could see the faces turning to stone in front of me as if we’d just entered a massive poker game, and they were holding the full house.

So I went back to my script, but now I was feeling the pressure. My mouth went dry, my face felt hot, and I oversold the first lines. Nothing. I could feel my stomach lurching, the feeling of oncoming death. I knew that feeling. I had been here before. But I didn’t expect it that night. And maybe that was the problem.

The set was an unmitigated disaster. It was as if the previous night’s audience had collectively decided, subconsciously, Hey, we love this guy, and we’re going to laugh at everything he says. And that tonight’s had thought, We despise this prick, and by gosh, we are going to let him know it.

I got through my full planned set of material, timed to be twenty minutes. Then I left the stage to a deafening silence. As I walked through the curtain into the dressing room, Martin Mor looked at me incredulously and said, "What the fuck are you doing? You’ve only done 12 minutes."

You see, Einstein was right. Time is relative. When you’re killing it, time flies. But dying is a melodramatic actor’s version of Shakespearean tragedy. It takes forever.

My previous performance suddenly seemed like a fluke. The comics and bouncers who had been high-fiving me earlier were blanking me. I made a hasty Retreat and walked briskly through the club because I felt a tangible threat of violence from a group of lads who recognised me as the loser who had just gone off on stage. British lads love weakness and can sniff it a mile away. I reeked of it.

I quick-stepped through the evening throng of sexual energy and the threat of violence, bought a fish and chips and some cans of Red Stripe, and went back to my room. Defeated.

After all these years, I still think about that night and what went wrong, and with the benefit of a few more years’ experience, I know exactly what it was.

On that first night, I walked out with the right amount of vulnerability (therefore likeability) and confidence. My tiredness from the working week meant I wasn’t so desperate, so eager. I knew what I was doing, but I also conveyed the demeanour of a nice person, a person to get behind and laugh along with. On the Saturday night, however, I walked out in arrogance. And while the audience did not consciously decide to hate me in that moment, subconsciously they already did.

That’s not to say arrogance doesn’t have a place in comedy. Comedians like Jimmy Carr and Anthony Jeselnik can exude arrogance on stage. But it’s a feigned arrogance. It’s a part of the gag. The audience knows this. They permit it so they can laugh along or directly at it.

Actual, unfiltered arrogance, on the other hand, is chum in the water. You may as well name your beneficiaries, get the affairs of your estate in order, dress as the ultimate German football fan, and head out to an English national-squad match, with a 100,000 screaming and intoxicated supporters of the Three Lions.

That is to say first impressions are metaphorically, and as in the above example sometimes literally, a matter of life and death. Those first few moments as you walk out on stage, as an unknown, are crucial. The audience is sizing you up. They are absolutely prepared to be your best mates, and they have actually paid to experience that sense of camaraderie, but if you turn away from them, distance yourself from them in any way, they are quite content to sit back and watch as you euthanise your entire set.

In short, the rules of stand-up comedy read like the rules of life. But everything is condensed. Time and space are compressed into a single moment beneath a spotlight. How you present yourself in the first few seconds on stage will determine how your night goes. And how you present yourself when meeting a new person or moving to a new country could very well determine how the rest of your life plays out.

Of course, this is all in hindsight. I would have to be taught this lesson once again because, unfortunately, I am one of those people for whom the light bulb above my head has to spark and fizzle and be fiddled with a few times before it finally receives its full electrical current and brightens enough to reveal that I’ve been standing in a pool of water.

• Brit Happens: Or Living The Canadian Dream by James Mullinger is available from Amazon.

Published: 7 Oct 2023