Every single line has to justify its existence

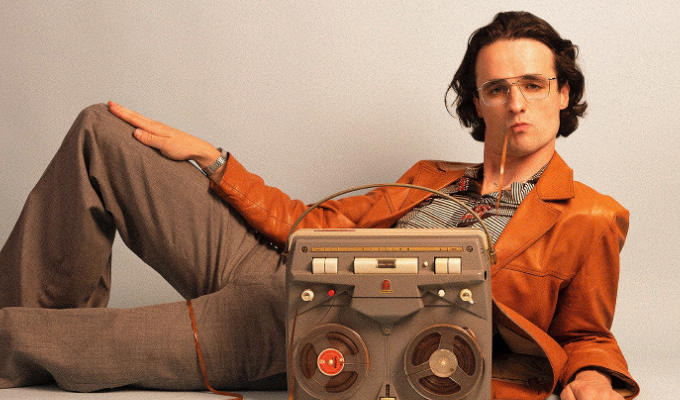

James Cary's sitcom writing tips

James Cary has co-created the BBC Three sitcom Bluestone 42 and the radio comedies Think the Unthinkable and Hut 33 – among other credits. He has just published the ebook Writing That Sitcom in which he shares some of the tricks of his trade. Here, as a taster, is his chapter on editing a script…You've got your Draft 0 and you think you might have knocked it into shape. Maybe it's a Draft 0.5. Or even a 0.8. The show makes sense, the scenes have jokes throughout at the end – and it feels like you've got something.

The bad news is there is much work still to be done. The good news is that you've done most of the hard yards.

At this point, you need to bear a few things in mind. The first is to remember the pile of scripts on the producer's desk. Her phone is ringing and she's reading your script. She's deciding whether to contact you because she's interested in you as a writer. But how interested is she? That all depends on how good your script is. Is it as good as it can be? No. Not yet.

One thing that will set your script apart from others is how tight it is. As a rookie writer it's hard to have confidence in your characters and jokes. There's a tendency to 'shove it all in' and hope that the producer sees something she likes. Cutting stuff may cut the one thing that arouses their interest.

No. She'll be interested if you can show that you've made decisions about what to include in your script and what to cut. She'll be more impressed if you deliver a tight thirty pages, rather than a baggy rambling forty-two.

Here comes an anecdote:

The Sin of Bagginess

As I've said in previous chapters, I learnt a lot about writing sitcom for television by writing six episodes of the fondly-remembered, critically-disliked sitcom, My Hero. I did this under the tutelage of some wonderful, kind and patient men who had made an awful lot of comedy between them ranging from May to December, through Game On to Vicar of Dibley and Alexei Sayle's Stuff.

Each draft of each script was read by the producer, exec producer, director, script editor and show creator. All these notes and thoughts were collated, interpreted and fed back by the producer, Jamie Rix, as truly delightful a human being as you could hope to meet.

One time I was having trouble with a draft of a script, so I sent in a Draft One that was very baggy indeed. Scripts for half an hour of telly are normally about 5500 words for me. Ideally a shade under. If you're playing around and have the luxury of time, a slightly longer script of 6000 is okay. (For radio, I tend to write slightly long, knowing that there isn't time to rewrite on the day, but there is time to make cuts, even before the recording itself). Let's cut to the chase. This draft of My Hero was about 9000 words. And I sent it in.

My reasoning was simple. There were lots of options on the script. Lots of ways to go. A number of possible funny routines. And ultimately, I didn't know what I was doing. And they did. So I was turning it over to them to decide where the funny was. In my mind, I was being humble and unpretentious.

They were perfectly nice about it. But frosty. I could tell they were profoundly unimpressed. And immediately I realised what an idiot I had been. I was being paid good money to write a script and decide where the funny was, what the story was and 'which way to go'. They suggested that I wasn't clear on what the story was and exactly what this episode was about. And they were right. I had no idea. And I'd abdicated my responsibility to write the darned show. I wasn't being humble and unpretentious. I was being lazy and spineless. And therefore unprofessional.

The iciness in the room thawed. They were gentle with me. More so than I deserved. But the moment stayed with me.

With My Other Hat On

Now I experience this bagginess from the other side. In my weak moments, I agree to read scripts for people. Quite often, the script is overlength and it's accompanied by an email saying 'I wasn't really sure what worked best, so I put it all in so you can decide'. Whenever I read that email, my heart sinks.

The first reason it sinks is I recall my own shame of doing this. And how it demonstrated my inexperience and laziness. I'm not saying that's why all people do this, it's sometimes sheer lack of confidence and a desire to 'show your working' - and is essentially a quest for approval.

It also makes my heart sink because I realise that this is going to be noticeably more work for me. I'm going to have to read a longer draft - twice - think about it for longer, feedback on more script, and ultimately think about 'which way to go' which takes up time and brainspace.

Then the rotten part of my heart kicks in and I think 'Hey, I'm not being paid for this. The writer should decide which way to go' and then the good part of my heart feels bad, but ultimately agrees. And I'm tired, cross and feeling guilty. Maybe other script editors are more patient, magnanimous and understanding. But that's usually my reaction.

I'd rather read a tight script where the wrong choice has been made, and it's been seen through and slaved over, than a baggy script where every choice and no choice has been made - and I'm effectively reading a 'Choose Your Own Adventure' sitcom script.

So, don't turn in hopelessly long drafts. Decide. Edit. Make some tough choices.

A rule of thumb in sitcom is that every line should be doing at least one of three things – often two of three things, and ideally all three.

1. Establish Character

The line should tell us about a character, developing or deepening our understand of them – or at least reinforcing what we know about them. I would suggest going through your script and making sure every single line is in character. Your characters should have distinct ways of speaking. If you cover up the name of the character and just read the dialogue, you should be able to tell who's saying the line.

In Only Fools and Horses, the temptation might be for all the characters to talk the same way. In terms of accent, that's true. But the words they choose to use are very different. Rodney and Del Boy are brothers – but they talk very differently. Del Boy's glass is always half full. His lines are brimming with optimism. Rodney's is always half empty. His lines drip with pessimism. The Uncle/Grandad speaks differently again. As does Boycie, who always calls Del Boy 'Derek' and uses ornate flowery language because he thinks he's better than everyone else. And Trigger is an innocent idiot who calls Rodney 'Dave'.

2. Develop the Plot

You need lines of dialogue which tell the story. A character refuses to co-operate with another character's plan. Someone breaks some bad news or throws up a complication. Or just throws up. Someone questions another character's motives or offers useless or bad advice. Again, these lines should be done in character, but they also need to be crystal clear so the audience understand what's going on.

3. A Joke

It sounds obvious, but it's a sitcom. You need lines that make the audience laugh. Some lines aren't especially characterful, and don't develop the plot, but they're really funny. That's fine.

The best kind of jokes, though, are the ones that are only funny because they're said by a particular character in their own unique way, in a situation that warrants it. The problem is that these jokes tend not work on their own, but our Buzzfeed/Listicle culture loves to snip out moments like 'Del Boy falling through the bar' or 'Grandad unscrewing the wrong chandelier'. Those jokes are really brilliant – and work in their own right. But they are the exception, rather than the rule.

When looking through Bluestone 42 for clips that could be used in trailers, to be viewed by people who didn't know the show, I found relatively few. There were plenty of jokes (if I do say so myself), but very few of them worked as lines in their own right. I was quite pleased because this showed our jokes were firmly embedded in their characters and situation.

In the end, one of the few lines from Series 1 that worked was Nick shouting at Simon 'You know why they're called booby traps? Because they get trodden on by tits like you!' But even that was a joke in character which developed the plot, as Nick was telling off Simon for stepping outside the area that had been searched for IEDs.

Go through your script again with this in mind. Ask yourself whether each line can justify its place in the show. If it's not a good character line, it doesn't advance the plot, and if it's not a joke, you have to delete it. Don't think about deleting it. Delete it. Or turn it into a joke. Or use it as an opportunity to express character.

It may be that you have a string of lines that don't do an awful lot. Or a scene feels slow. Sometimes you can see a little exchange of seven lines and you reckon you could achieve the same in four or five without losing clarity – and plausibility. Do it. Look to finish a scene earlier. Or start it later. Is a character repeating information we already know? Why say it again? Cut it. Every single line has to justify its existence.

Done that? Good, you'll need to do it again, but I'll explain how in a moment.

Cutting Jokes

What? Cut jokes? Are you crazy? I thought we were cutting boring lines and stuff that wasn't needed.

Calm down.

In a TV show, everything happens for a reason. The audience subconsciously know that. They expect everything in a show to be significant. Hopefully, they're not thinking about this too much. A funny set-piece scene is great, but if it doesn't lead anywhere or advance the story, the audience might be confused, or expect a development that never happens. You have to do something about that expectation.

In an interview with Chortle, Mitchell and Webb pay tribute to the writers of Peep Show, Sam Bain and Jesse Armstrong, saying "They'll throw anything out, however funny it seems, if it doesn't fit what they see as the right arc for that story, episode or series, they will throw it out without a qualm." Webb agrees, saying, "They are amazing rewriters. That's the trick, to be really unprecious about really funny stuff."

Mitchell goes on to say that as a writer-performer, he holds on to things that get laughs extremely tightly. He says Bain and Armstrong are at an advantage as non- performers, since they're able to be more ruthless.

It's not that good writers are natural geniuses for coming up with suitable jokes and scenes that form a story. Clearly talent and experience are very useful and can save time on occasions. Really good writers understand they need to churn through dozens of ideas until they come up with the right jokes for the right story that'll get from A to B (and back to A again) in the right way - even if it means junking really funny stuff because it's not helping tell the story.

As you go through your script, you should be asking yourself what each scene is achieving and what each line is achieving - and how it relates to the central story or your subplot. When rewriting, a line Richard Hurst and I often say to each other is 'I'm not sure this line is working hard enough for us' - which means the line is woolly and doesn't move things along. If your script is really good, there's no room for lines like that.

As you go through your script, you should be asking yourself what each scene is achieving and what each line is achieving - and how it relates to the central story or your subplot. When rewriting, a line Richard Hurst and I often say to each other is 'I'm not sure this line is working hard enough for us' - which means the line is woolly and doesn't move things along. If your script is really good, there's no room for lines like that.

So, here's what to do next. Print your script out, take a pen and sit at a table where there are no distractions, laptops or smart phones. Go through it and cross out stuff that isn't part of the story. Including jokes you don't really need.

Then go back to your computer, make the cuts, and trust yourself to fill in the gaps or make up the time with new lines and scenes that are relevant, characterful – and therefore much funnier. You will end up with a much leaner, meaner script.

So if you're still up for this, let's get going. Cue Opening Titles.

• Writing That Sitcom by James Cary is available from Amazon as an ebook, priced £4.99. Click to buy. He also blogs as Sitcom Geek.

Published: 15 Jul 2015