'If you want to get started in comedy, steal'

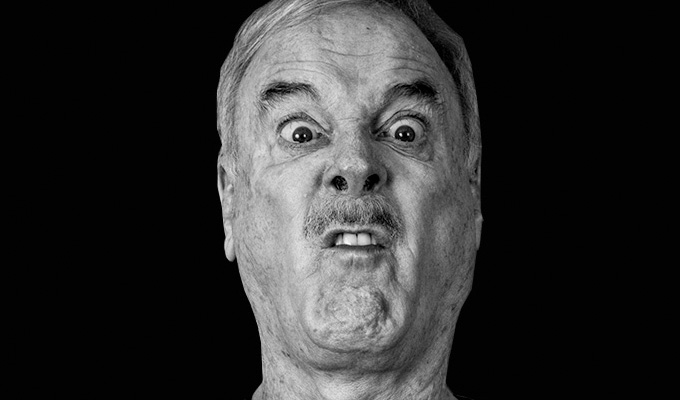

John Cleese on his career, his plans – and some trade secrets

He's had one of the most enduring careers in British comedy – but John Cleese says he owes it all to a student landlady.

The Python and Fawlty Towers legend got his first break with the Cambridge Footlights – but he only became a regular part of the performers' club because its base was so close to his second-year undergraduate room.

'Had I not got digs 100 yards from the Footlights Club, I doubt if I doubt if I would have spent any time there at all,' he says. 'If I'd have to cycle three miles to lectures every day and out again…

'But as it was, it was most convenient place for me to go and have a drink with people I liked best at Cambridge. When it was bloody cold, as it usually was, I could have just put on a coat and got there there in 60 seconds.'

It was a fluke he wound up so close to the club – only a landlady called Mrs Risely having an argument with Queens' College and barring their students from her coveted city-centre rooms opened up a last-minute vacancy for Cleese.

'Had I not been there, would I have been a comedian? ' he ponders now, as we sit in the offices of publishers Random House, which has just released the first volume of his memoirs. 'I probably would have finished up a lawyer, writing comedy on the side for Punch magazine. I might eventually have given it a go as a full-time trade but never performed.'

Would he have liked that life? 'No, I don't think the law would have suited me. I don't think I would have enjoyed it very much. I don't like the manipulative stuff that goes on behind the scenes, although intellectually, it's interesting.'

However, one of the happiest times in his life, as described in So, Anyway… is when he taught at his old school, St Peter's in Weston-super-Mare, in a 'gap year' before going up to Cambridge.

'I always felt – and this isn't in the book – that if the worst came to the worse I could always go back to teaching,' he says. 'And i thoroughly enjoyed that, so the worst was never going to be very bad.'

As described in the book, Cleese was part of the 1963 Footlights revue A Clump of Plinths, which was so successful at the Edinburgh Fringe that it was renamed and taken to the West End and on tour to New Zealand and Broadway.

He then had a brief stint with the Broadway musical Half a Sixpence with Tommy Steele – to this day his only stage acting credits outside of Python – before returning to the UK to appear in the radio show I'm Sorry I'll Read That Again; to write and perform with David Frost on his TV programmes; and to create At Last The 1948 Show with Tim Brooke-Taylor and Marty Feldman, before the formation of Python, which is, more or less, where his autobiography ends.

He admits there was 'never a better time' to be involved in TV than the Sixties and Seventies – especially as the rigid class distinctions (he defines himself as coming from the middle-lower-middle-class) and ingrained deference to authority were beginning to crumble, led in part by the new wave of satire started by Peter Cook and his Beyond The Fringe colleagues,and subsequently embraced by Frost.

'Life was loosening up, there's no doubt about it,' Cleese says. 'But we all got a bit fed up with the satire boom and almost reacted against it.

'We were will never really part of it. We never really knew a lot about politics, or indeed social matters. We were not a very highly intellectual, highly informed bunch. We were just average. So we never got into that, and anyway the sort of humour I liked best was farce.'

He also full of praise for BBC executives of the time (except head of light entertainment Tom Sloan who 'didn't begin to get' Monty Python because he 'wasn't that bright'). 'Most started as floor managers and worked their way up, and as a result they were well educated in comedy, they really understood comedy,' Cleese says. 'So we would accept their judgements; there have been very few times when executive judgement has been better. Whereas, based on what young comedians say now, these commissioning editors don't seem to have any experience of, about it says don't seem to have any experience of comedy at all.'

He believes that in those days of fewer channels, broadcasters were prepared to take more risks – and spend more money – because they would still be guaranteed a reasonable audience.

'They are more risk-adverse now because audiences are much smaller,' he said. 'In my day, fewer channels didn't mean you didn't get whacked now and again [by the critics] but there was a general feeling that there were enough viewers around. As viewing figures went down, the result was to make cheaper and cheaper programmes.'

'If you want to get on in TV now as a producer, you have to be able to make a lot of shows in a short period of time and not be required to pay too much to people with talent.'

That said he adds, slightly morbidly: 'I know there's some good stuff out there but I don't have time to watch it, because with ten years left to live I'd rather read books.'

Cleese, 75, says that when he first started in comedy he was 'a neurotic perfectionist; I used to worry a lot'. But that gradually he relaxed as he learned through experience.

'You also learn that your opinions are not always right,' he says. 'Young people tend to be rather arrogant about their judgment and then as you get older you begin to realise that your judgment is a bit more fallible.

'Then you start listening to audiences and you realise how different audiences can react differently to exactly the same material. If there is a piece of film that they all laughed at last night but were not laughing at the night before, is that funny or not funny?'

Cleese likes to think of himself as a writer first, and performer second. 'I don't think that there is any doubt that writing is the creative bit and the acting is more interpretative,' he explains. 'There are some great performers who can claim to be more creative but basically writing is much more difficult. And very, very few people can really write good comedy. But a lot of people can write a good drama.'

For those embarking on a career in comedy, he has one simple word of advice: steal.

'I'm not so much talking about stealing a particular joke, because you don't learn anything from that, but stealing a style,' he said. 'And I'm just staying steal at the beginning, as you get better you don't need to steal.'

Cleese himself says he learned by writing out Peter Cook and Dudley Moore sketches from recordings, 'and by doing that I began to see why it was funny. It was very educational.'

He also says that repeated listening helped him understand the nuts and bolts of comedy. 'To analyse something you have to watch it in enough times not to be emotionally affected by it. While you're still laughing at it, you cannot see clearly what is being done.'

He also admits that a life dedicated to comedy means 'you do get to know all the jokes', so it's harder to laugh. 'It's relatively unusual now for me to come across anybody who is very funny very fresh and very new. I think there are some very good young stand-up comedians about, but I don't think of stand-up as being the apex of comedy, compared to writing.'

'When Eddie Izzard does a set, that is the apex of stand-up, but if I were to be remembered for something I would rather it be for a great TV series or a great film than for stand-up – but it's a question of taste; it doesn't mean I'm right.'

He recalls seeing a stand-up, who he doesn't name, in an arena in San Jose and being baffled at how the audience cheered and punched the air triumphantly at every joke, but rarely laughed.

'I thought he was terrible,' he recalls, 'but it was fascinating because you're getting a great reception from a crowd who I would say had no discernible sense of humour.'

But he adds that 'humour is very subjective and you can forget that. You can't say something is funny or not funny, you can only say it's not funny TO ME.

'Comedy is so complicated; it's very hard. Journalists are always trying to come up with one-sentence descriptions, and it's ludicrous; it's far more complex than that. People who analyse jokes seldom take into account the fact that joke told badly is not funny. The awful thing about comedy is that until everything is right, it isn't funny.

'That's why watching rough cuts of movies, unless you get experienced, can be pretty devastating because most of it doesn't seem very funny. You have to sit there thinking 'can we fix that?' as you go along, knowing it's going to be all right. You have to trust your instincts.

'With a movie, if you're writing it from scratch, it takes at least two and a half years and during that time there are only five times when it's funny: when you first write it, at the first read-through, at the first rehearsal, when you first shoot it, and then when you finally edit it.

'The rest of the time you just have to feel it, knowing the rhythm is right, all that stuff. It's almost muscular, it's so deeply ingrained.'

Asked whether that means comedy is harder to do if you're younger, he said: 'Like anything, you need two things you need some talent a lot of practice.'

Not that his instinct is always correct; he recalls the scene in Life Of Brian involving jailers with speech impediments. 'I just thought to myself, "This isn't funny,"' he says. 'So I didn't bother to go on set as we normally did to watch and make because I just thought we'd end up cutting it.

'In the end it wound up being one of funniest scenes in the film. Sometimes you can be completely wrong.'

Conversely he sometimes considers something 'terribly funny' but few others agree – and points out a section of his book talking about bombs falling on Weston-super-Mare that 'was in all the papers. Especially the Weston Mercury' which he thought hilarious but no one picked up on.

He said: 'I think if people read a book like this when they are in an anxious state of mind, or in a hurry, they like to read it like information. If they read the same passages when relaxed, it could be much much funnier than they realise.'

On striking a balance between being entertaining and 'baring his soul' in the book, he says: 'I don't see any point in writing an autobiography if you don't reveal something about yourself – what would be the point?

'For me, I don't want to reveal confidences. But I'm happy to reveal what my reactions are in certain circumstances which might be sad or might be hilarious. Because that's what life is like, it's not all happy and it's not all sad.

'If you mention sad things people start thinking you're getting morbid, but it's part of the whole texture. Life is paradoxical in a way that most people, especially British journalists, don't seem to understand. In every relationship where there's love there's always a bit of what Freud would have called hate. There's always a bit of positivity and a bit of negativity.

'Brothers like the Pythons would kill anyone who tries to attack us, but then we are always teasing and bitching at each other when we are in the the room.'

As for what else Cleese has planned for the ten years he expects to live – there's another volume of memoirs to be written 'but not for a bit because I want to come to it fresh.

'The next thing is I've found a very funny French farce which I've had translated literally into English and I am going to be adapting that in the sun in the next few weeks for the stage.

'I don't want to tell you the title because I don't want anyone else to pinch it. But it's a good old-fashioned French farce. It's brilliantly plotted. The dialogue is not that great – I can't judge how good it was in the original French, but the English version is just dreadful so I am going to rewrite it all, change a little bit of the plot, and see if if that can go out because people like farce. Farce gets bigger laughs than any other kind of comedy.'

'I've also written the first draft of the book for the musical of a Fish Called Wanda with my daughter, but that's going to take a long time.'

• John Cleese: So Anyway is out now, priced £20. Click here to buy from Foyles for £14.

Interview by Steve Bennett

Published: 11 Dec 2014