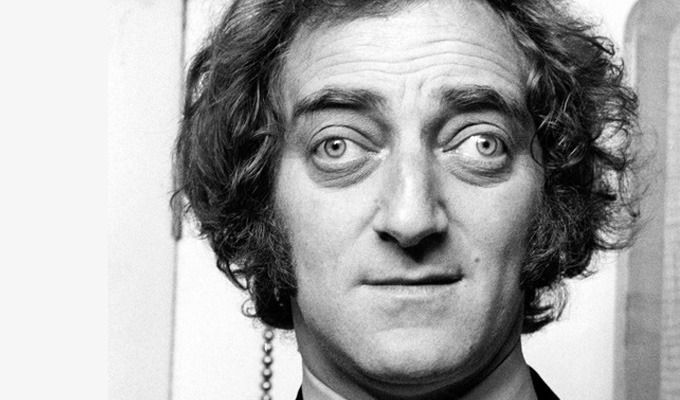

Not just a gagging gargoyle

Andre Vincent pays tribute to Marty Feldman, the unorthodox comedian

‘Comedy, like sodomy, is an unnatural act.’

If you mention Marty Feldman today, the likely response will be a Young Frankenstein impression: ‘Hump, what hump?’ or a smack to the side of the head in recognition of his character quirk in Sherlock Holmes’ Smarter Brother. That, or a burst of ‘Kangaroo Hop’. But before his film career in Hollywood took off, Marty Feldman was an integral cog in the engine of British comedy: not only an outstanding performer but also a uniquely gifted writer.

In 1950s and 1960s Britain, anyone who was anyone in comedy would have performed lines by Feldman. He gave Bernard Bresslaw his catchphrase, ‘Ullo, it’s me, Twinkletoes’. He wrote the famous ‘class sketch’ for the Frost Report: ‘I know my place’. He penned the tagline ‘Hello, honky-tonk’ for Dick Emery. He was even part of the writing team and an original performer of the Four Yorkshiremen from At Last The 1948 Show: ‘...you try telling that to the young people of today. Will they believe you?’

Feldman was born in Canning Town, East London, to a family of Jewish immigrants from Kiev. London life was very hard for them - Feldman remembered, as a child, fleeing several of their homes in the middle of the night to escape the family’s rent arrears. He had a solitary upbringing, rarely mixed with other children and had no interest in anything other than music, particularly jazz and klezmer.

Like many city children during the war, Feldman was evacuated to the countryside. Here he discovered the delights of rural life - though after the rabbit he had been frolicking around with one afternoon appeared on his dinner that night, Feldman became a committed vegetarian. (Years later when asked about his diet, Feldman declared ‘I won’t eat anything with intelligent life - but would gladly eat a network executive or a politician’.) During the war years, Feldman and his fellow evacuees were entertained by local screenings of silent movies. Feldman adored their physical comedy and slapstick, and none more so than that of Buster Keaton.

’I feel about Keaton the way an organist thinks of Bach.’

Feldman’s father prospered during the war, and he moved the family to a better life in north London which was not, however, so easy for his young son. Feldman was constantly bullied at school, often about his ethnicity. On one occasion, a child poked a pencil in his eye causing amblyopia (‘lazy eye’). At another school a cricket ball was thrown in his face, breaking his nose. In return, he broke the nose of the child who threw the ball, for which he was expelled. In fact, Feldman was expelled 12 times by the age of 15. He boasted: ‘I’ve been thrown out of some of the worst schools in London.’

The one school subject at which Feldman shone was English. He showed a particular talent for writing, but even that led him into trouble when, at 11 years old he wrote a poem for a class competition. The poem appeared to be so good that the teachers accused Feldman of plagiarism. Despite constantly pleading his innocence, he was punished and as a result, began to resent and reject formal education.

At 15, disillusioned with life, Feldman left home and started to travel. The next five years read like a Boy’s Own adventure story: he would be deported from France three times, be a stooge for a West Country hypnotist, a fairground barker and even a getaway driver for an east-end villain. In fact, Feldman maintained a dubious relationship with the underworld throughout his life. While performing in Belfast as a young man, Feldman was requested to appear at the stage door by some large Northern Irish heavies, who took him to a pub where he met the legendary pugilist and gangster, Silver McKee. McKee wanted to have a drink with a man who ‘mixed with his sort in London’. On another occasion, he managed to secure seats for the 1966 World Cup Final from his shady associates. They turned out to be two rows behind the Queen.

Feldman began to spend more and more time in fashionable Soho. He broke into the Tudor-style Gardener’s Hut in the centre of Soho Square and squatted it for many months. He stole philosophy and history books to read, before selling them on to secondhand stores. He also conned the Soho jazz scene into thinking that he had been a gifted trumpet player, now unable to play because of tuberculosis. Then he wormed his way into the London poetry scene where he convinced the literati that he was the new prodigy of the art, and with the support of Dylan Thomas was even published several times. Graham Chapman said of Feldman’s youth: ‘He was a BA, first class honours with distinction, from the University of Life’.

’Money can’t buy you poverty.’

Also during this period, Feldman landed a summer job working the rides and stalls at Dreamland in Margate. One season he performed in a Red Indian act (lassos, knife throwing, whips…) with an old-time music hall performer and knife twirler, Joe Moe. Joe was a very large man who could play ukulele and sing Hawaiian war-chants. Also working the fair that year was Mitch Revely, a red-haired clarinet-playing midget. Together, the three of them looked hysterical and this perfect combination of oddballs united as a triple act, Morris, Marty & Mitch.

’Humour evolves as you evolve as a person, you do it for the same reason you paint a moustache on the Mona Lisa. It’s a spontaneous demonstration of anarchy.’

Over the next few years, the threesome toured the variety circuit and US army bases, offering music, slapstick and knock-about dance routines, which by all accounts were dreadful. Sometimes the theatre manager would see the act on the first night and pay them off for the week, as happened in Swansea on Feldman’s 21st birthday.

Advised that their services would not be needed, they were however, required to appear for the curtain call before receiving payment. Smoking at the stage door prior to this finale, Feldman was headbutted by a remonstrating midget who accused him of taking advantage of Mitch Revely. Mitch himself saw the assault and joined in the fight, and the two midgets had to be prised apart. When Feldman and Revely took their final bow - both covered in blood – it was before an audience who had no idea who they were, and who assumed they had been fighting each other. Feldman decided that the act had to end.

In the early 1950s - the final years of variety - Feldman saw the likes of Jimmy James, Max Miller and Freddie Frinton performing their comedy. Inspired by these great talents, Feldman moved back home and started writing his own brand of humour.

Comics entering The Palladium for a night’s work were sometimes confronted by Feldman as he tried to sell them his gags. He also wrote and submitted complete episodes of The Arthur Haynes Show to the producers but was never hired. He finally managed to get one of his sketches onto the radio show Take It From Here, though Feldman himself described it at the time as ‘…heavy on charm - which means no-one laughed’. But the opportunity did introduce him to a fellow writer on the show, Barry Took, with whom he discovered a similar sense of humour, and they struck up a friendship.

Feldman’s employment as a comedy writer developed further - first, BBC radio’s Educating Archie featuring ventriloquist Peter Brough and his doll Archie Andrews; then contributing to Barry Took’s Take It From Here, in particular The Glums section. As a result, Took and Feldman were asked to write for the Harry Worth/Peter Jones radio show We’re In Business and Granada’s top-rating television series, The Army Game.

The popularity of the show’s Sgt. Major Snudge and Private Bisley led to the creation of a spin-off series, Bootsie & Snudge, which Feldman and Took wrote together. Thirty-nine episodes - more than 950 minutes of script – were turned around in ten months, and this while both of them were still writing sketches for other radio shows. It’s not surprising that soon after this intensive stretch, Feldman became erratic and moody, and was then diagnosed with a severe hyperthyroid condition requiring surgery. The resulting operation was a success, but a noticeable side-effect was his characteristic bulging eyes.

The pen is mightier then the sword and considerably easier to write with.

Feldman continued to write for Bootsie & Snudge while convalescing, and although additional writers were hired to share his workload, his distinctive style often stood out: one episode had Bootsie in conversation with an ant, which was pure Feldman. During this period, he also wrote for the BBC’s Comedy Playhouse, Terry Scott’s TV specials, and Round The Horne which gave us such characters as Ramblin Syd Rumpo, a West Country bumpkin, and Julian and Sandy, two flamboyant camp characters who spoke mainly in Polari (a gay slang likely to have been picked up by Feldman on the streets of Soho). The show was enormously successful and, 50 years later, its recordings are still among the BBC’s best sellers.

In 1966, Feldman became chief writer for the BBC’s new TV series The Frost Report, a satirical television show hosted by David Frost. Notable for introducing John Cleese, Ronnie Barker and Ronnie Corbett to television, it also had a sensational roll-call of writers including Barry Cryer, John Law and Frank Muir.

The show’s success led to Frost himself financing one of the performers, John Cleese, and two of the writers, Tim Brooke-Taylor and Graham Chapman to make a sketch series. This was At Last The 1948 Show, the title being a wry comment on the protracted decision-making of television executives. All three were keen to involve Feldman as both writer and performer in the project, and although Frost was initially unsure how the audience would take to his strange appearance, the show was a triumph – as was Feldman.

’I think the success went straight to my crotch.’

In 1968, Feldman was given his own show, Marty, by the BBC. Its relatively big budget allowed him to assemble the best writers of the day and to film outside broadcast sketches involving complex stunts. Feldman claimed later that ‘The Loneliness of the Long Distance Golfer’ sketch was not only the greatest thing he ever created, but also the closest he ever came to emulating his hero, Buster Keaton.

The series was a triumph – it won many awards, made Feldman a celebrity and resulted in him becoming the drinking, drug-taking, flower-powered man of the moment. He could regularly be spotted in the fashionable clubs of the west end, chatting with the Beatles or the Stones, and he never seemed out of place.

Unsurprisingly, becoming the darling of comedy led Feldman to movie roles. He acted with an all-star cast in The Bed Sitting Room in 1969, and then in Every Home Should Have One, written with Took. It would be the last time that they worked together since their partnership was suffering from ego clashes and general exhaustion. Took recalled years later: ‘It felt like breaking up a lovers’ relationship, a real divorce.’

Feldman was unaware that the BBC had been selling some Marty sketches to US television until, as a result, he was asked to appear on The Dean Martin Show and promptly offered a series by ATV. This joint US/UK venture spawned fifteen episodes of the Marty Feldman Comedy Machine.

The show soon began to attract American fans and one of them was Gene Wilder, who offered Feldman the part of Igor in his new movie Young Frankenstein. Feldman jumped at the chance of working with Wilder and director, Mel Brooks, despite the constraints of it being someone else’s baby.

Transylvanian Station was the first scene to be filmed, but before even an hour was in the can, Feldman started improvising. Playing with the meaning of ‘walk this way’, he handed Wilder his stick so Wilder might imitate his action rather than simply follow him, which had the film crew in stitches. Brooks wanted to keep this in the edit, but Feldman was adamant that such an old music hall gag should be cut. The first screening proved Brooks’ instinct to be correct, since the audience loved the line. Indeed, it became a cult favourite and later inspired the Aerosmith song Walk This Way.

’I don’t want to be a director, I want to direct. There is a difference.'

Wilder and Brooks used Feldman for their next films, Sherlock Holmes’ Smarter Brother and Silent Movie, the latter being a perfect vehicle for Feldman’s natural slapstick. It also gave him the opportunity to meet many of his childhood idols including Marcel Marceau, Sid Caesar and Harry Ritz.

Both movies did very well, after which Universal Pictures offered Feldman a six-film deal, and five million dollars to make his first feature. Fumbling the pitch description of the film he wanted to develop, Feldman ended up releasing The Last Remake of Beau Geste in 1977 – when all along it was a remake of The Four Feathers that he’d intended. Still, he got to be the writer, star and director. Feldman wrote and directed one other film, In God We Tru$t, a biting religious satire starring Andy Kaufman and Richard Pryor. The film was a production and box-office disaster, and Universal scrapped Feldman’s contract.

He spent the next few years in what he would refer to as ‘Hollywood wilderness’, and left to make some rather soul-destroying appearances on TV shows such as Hollywood Squares, The Johnny Carson Show, US Against The World, The Muppets and Fridays.

He spent the next few years in what he would refer to as ‘Hollywood wilderness’, and left to make some rather soul-destroying appearances on TV shows such as Hollywood Squares, The Johnny Carson Show, US Against The World, The Muppets and Fridays.

'I won the award for being the best loser.’

In 1982, Feldman died in a hotel room in Mexico City from a heart attack. He was, at 48 years old, making his movie comeback on the film set of Yellowbeard. Many theories exist as to the cause of his death: lung problems caused by the high altitude of Mexico City, food poisoning, even an overdose. But Mel Brooks’ summary of Feldman’s lifestyle might suggest the true reason: ‘He smoked sometimes half a carton (six packs) of cigarettes daily, drank copious amounts of black coffee, and ate a diet rich in eggs and dairy products.’ He is buried in Forest Lawn Cemetery, Hollywood Hills, next to Buster Keaton - you can’t get closer to your idol than that.

’I’m too old to die young, too old to grow up.’

Marty Feldman endured poverty, lovelessness, anti-Semitism, chronic boredom and waking up to that face every morning. Today’s psychoanalysts would have a field day unpicking his development as a comic, seeing it as an inevitable outcome for this neurotic Jewish boy. Whatever the reasons, he formed the backbone of the satire boom usually attributed to the Frost/Oxbridge generation: not just a gagging gargoyle but one of the most inventive minds ever known to comedy.

Published: 27 Feb 2014