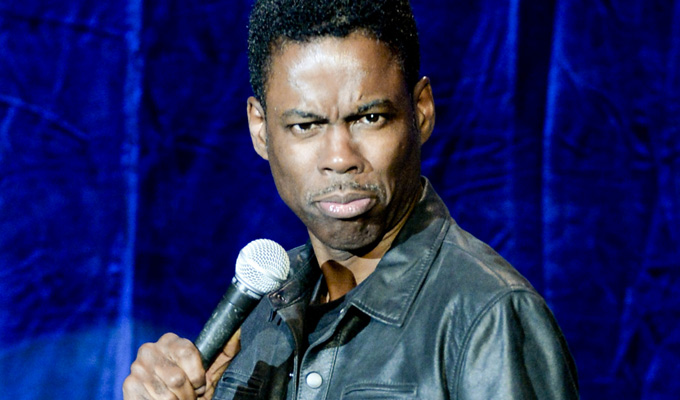

Chris Rock changed my life

Lorcan Mullan on Bring The Pain, 20 years on

I think when most people discover their life's passions it is born from when they witness a work, or a moment in time, in their formative years that forever stays in their minds and they, consciously or unconsciously, seek out another moment like that for the rest of their lives.

For my love of music it came from listening to Radiohead's OK Computer and Eminem's The Slim Shady LP. For my love of cinema it was M. Night Shyamalan's Unbreakable (which I now refuse to re-watch for fear of being very, very depressed) and Fernando Meirelles's City of God. For my love of football it was Aston Villa's League Cup triumphs in 1994 and 1996, followed by the Euro 96 tournament.

For my love of comedy it first came from falling asleep listening to my Dad's old collection of Jasper Carrott LPs. An even greater head-turning moment happened a few years later when I was stuck at home, alone and bored. In this lonely atmosphere I flipped channels till settling on the Paramount Comedy Channel and saw a pair of feet marching with purpose towards a raucous crowd.

Mixed against the walking were flashing images of classic comedy albums from the like of Richard Pryor, Bill Cosby, Steve Martin and Woody Allen. Those images were the faceless performer's homage to his heroes, a point towards his eclectic taste in comedy, and a statement of intent to be seen as an equal to the best performers of the last 40 years.

Quentin Tarantino had done a similar thing a few years earlier in the opening credits to 1992's Reservoir Dogs, and, just as Tarantino achieved with that low-budget crime flick, Chris Rock would proceed to lay down a marker that nearly every stand up has tried to match ever since with 1996's Bring The Pain.

Today marks the 20th anniversary of Bring the Pain's HBO premiere, I personally caught the show some time around 1999 or 2000, and only initially recognised Rock because of his voiceover work as a hamster in the 1998 Eddie Murphy remake of Doctor Doolittle. It's similar to how my first encounter with the Beatles came when I watched their 1965 film Help! on the telly. My only initial observation was 'so this is what Ringo Starr did before he narrated Thomas the Tank Engine'.

I re-watched Bring The Pain recently, and listened to the album version Roll With The New, to try to better understand why this was my Road to Damascus experience for stand-up. The simple answer is that it really is a masterclass in performance, and an example of finely honed material that can capture a moment in time better than any other, usually less straightforward, artform can seek to achieve.

It seems appropriate that the show would start with Rock's feet, because there is no better walker in all of stand up. He marches, prowls, struts, stomps and skips around the stage for almost the entire hour. He covers as much space as a box-to-box midfielder over 90 minutes in a high-paced game of end-to-end football.

His vocal tics provide an emphasis to his points that the likes of Ian McKellen and Benedict Cumberbatch spent years training to achieve. He takes a word like 'crack' or a phrase like 'it was a day of positivity' and uses each 'k' 'd', 't' and 'p' sound with a precision of intent as a means of pointing out the absurdity of Marion Barry's presence at the Million Man March. It would make you laugh without even knowing who or what Marion Barry and the Million Man March were.

While I didn't know who Barry was at the time (and had to do a quick Wikipedia read just now to remind myself on some of the details left out in the routine), Rock's quick summary of his position as a politician caught smoking crack, serving time in prison, and then re-elected to Mayor of Washington DC, the nation's capital, provided my favourite line of all the comedy that I've ever watched or heard.

‘Smoked crack got his job back. How the hell did that happen? If you get caught smoking crack at McDonald's you can't get your job back!’

In one line he summarises the plight of the minimum wage working class, the hypocrisy of the career politician, the divide between perceptions of crime when viewed through the prism of income and class, and the absurdity of a democratic system that the working people prop up by voting in the aforementioned crooks and liars. [Insert obligatory Donald Trump reference here].

When I champion Rock to others I am often greeted with the assumption of his material not going beyond 'White people drive like this, black people drive like this'. As time goes on, I've come to realise how this attitude inherently proves why Rock and most other black comedians choose to root a lot of their material in race.

I'm not the only person to write an online article in 2016 (or even this specific day or hour of 2016) that points out how Western culture has been defined by the outlook of the straight, white male. Anyone not fitting into this criteria is reminded of that fact on a daily basis, both explicitly and implicitly.

When white men are confronted with a work that's not explicitly about them when they feel it should be (e.g. the new Ghostbusters film) they pitch an online fit of an equivalent raucousness to the 2011 English riots. This need, whether they are conscious to it our not, for white men to be placated at all times therefore informs nearly every facet of how they live their life. Until recently most lived in a blissful ignorance about our dominance of culture and would therefore feel justified in moaning that a black man did routines about life as a black man.

Back in 1999, it jarred me slightly when there were moments in Rock's routines that sought to exclude me. ‘What the fuck did we win?!’ he yelled only to black people who celebrated the then-recent exoneration of OJ Simpson. ‘White people are on welfare too, but we can't give a fuck about them.’

Was this Rock saying that he didn't want me to listen to his comedy? That it wasn't meant for me? I think Rock's reaction would be ‘no’ to the first question, and ‘sort of’ to the second. I can listen, but I have to understand that it's not for me to take and use myself. I should only be an observer and listener. There's a cultural copyright.

So this is where we have to address what will forever be Bring the Pain's main claim to fame. 'Ni**as vs. Black People' is perhaps the most daring, and misunderstood, stand-up routine ever performed. Earlier in the show Rock had said to his detractors in the audience "Boo if you want. You know I'm right". That's his overall attitude throughout this show. Chris Rock has things to say, and they may hurt. He has come to bring the pain.

In Roll With The New, Rock interspersed his stand-up with thematically relevant sketches, usually about the reception that his show has, and characters offer complimentary and contrary viewpoints. The one that follows Niggas vs. Black People has a series of white people approach Rock in the belief that the routine has allowed them to say racial slurs to his face, deride black people, and expect him to be on their side.

Years later, Steve Carrell's Michael Scott character from the US version of The Office faces repeated HR infractions for quoting the routine verbatim to his co-workers. It's appropriate that a clueless dolt like Carrel would know this routine word-for-word without understanding its potency in the slightest. He thinks a black man has given him permission to say what he's always wanted to say.

What the routine was meant to be about was self-reflection. This was a verbose performer using his great skills in thought and phrase to turn the mirror on his own cultures, revealing a slightly uglier reflection than they will admit to having, and arguing that some of the worst stereotypes that they suffer come from a truth among the actions of a minority within their minority. Actions that harm them because of the prejudices of those in power thinking that they have a right to also deride and distrust the majority of ‘black people’ that do not fit Rock's description of ‘Niggas’.

As a child of Irish Catholic heritage, growing up in the 1990s, myself and my mother were never once associated with, or confronted and expected to explain or denounce, the actions of any of the IRA terrorists. The same can't be said for most Muslims in this, or any other, country where they are a minority.

Perhaps the first white comedian to truly understand Rock's routine and create an appropriate equivalent was his own frequent collaborator (and, in Rock's own words, ‘the niggariest white person I know’) Louis CK. His routine about being white from 2011's Live at the Beacon Theatre is about accepting that white privilege exists, and the intention of most white people to enjoy it for as long as they can.

It's a joke understood about an experience for white people in one way, and for non-white people in a different way. ‘We have a table waiting right here for you, sir,’ is probably my second favourite stand-up line ever after Rock's McDonalds bit.

Rock and CK come from a history of US comics who revel in taking a controversial stance and then justifying it to an often wary audience with their own internal logic. Rock will often use a verse/chorus structure of sorts, returning back to the contrary line of thought (‘I'm not saying (OJ) should have killed her... but I understand’) after taking it down a variety of angles, exhausting each separate idea of all variables, before returning to that core point.

This attitude is present in the works of George Carlin, Patrice O'Neal, Bill Burr and many others. British-based comics try it too but the most popular ones who get the DVD releases and the Live at the Apollo shows mostly take a conventional, or apolitical, stance. There is no popular comic in this country having observations referenced and discussed on news and current affairs, or quoted by politicians, like Rock's routine was in the immediate aftermath of the show. As Rock said in Life magazine a few years later, ‘Next thing they were talking about it on C-SPAN, and I'm, Huh?’

Even politically minded comedians in this country usually come from a hardened left-wing position, a post-Alternative comedy mindset of ‘Tories bad’ and having nothing much else to offer other than that. The backlash against that in the 1990s and 2000s lad culture and ironic racism/sexism, etc. never offered anything other than saying a naughty word and thinking you can get away with it because you couldn't possibly mean it. Offensiveness was only there to make money, not a point. It paid to be contro-mercial.

If you want an example of a British comic, with little to no mainstream exposure, who is truly trying to ruffle the feathers of a liberal audience and conventional thinking (and who has cited the likes of Rock, Burr and O'Neal as direct inspirations) then check out Alfie Brown's 2014 show Divorced from Reality (and My Wife), particularly his bit about the age of consent. He's not the complete article yet, but he's probably the comic I most look forward to seeing with every passing year I visit Edinburgh for the Fringe. And I fucking hated the first show of his I saw...

In Bring the Pain, Rock said he would never hit a woman, but that ‘I'd shake the shit out of one!’, arguing that ‘no one's above an ass-whuppin’. He pointed out that drug dealers aren't really to blame for society's need to get high. In his 1998 follow-up, Bigger & Blacker, he admitted that was conservative when it came to crime (and liberal on strippers). He even accused Hilary Clinton of being responsible for her husband's infidelities in office because, as the First Lady, ‘she should be the first person on her knees, suckin' his dick!’

He obviously doesn't mean half, or maybe all, of these things, but he sees it as his job to prod and poke at people's beliefs and conventional wisdom. If laughter is derived from people going against those natural inhibitions, it's natural that a lot of stand up should be saying something that you'd never thought you'd hear until you heard it, and it causing that involuntary laugh.

Nowadays it feels like we're all trying to fight against exposing those inhibitions harder and harder in order to meet some almost Messianic moral ideal, a higher place for us to look down on others that don't meet our exacting ethical standards. And to blog about them.

There are nuances to the way that we as individual's view life that are perfect for stand-up. If Bring The Pain were to be released today, though, it depresses me to think of the deluge of think pieces and blogs it would have garnered from people from all across the political spectrum decrying Rock (who no longer plays college gigs for reasons such as this) for one part of his routine or another that didn't match their own personal viewpoint and should therefore everything he says should be dismissed entirely.

For all this, though, the legacy of Bring The Pain is still felt positively to this day in our culture and comedy. Barack Obama referenced it when campaigning for the presidency in 2008, Jay-Z repeated the line ‘Grand opening, grand closing’ in his go-to show-ending tune Encore and Rolling Stone ranked the show as the second greatest stand-up special of all time.

I would personally place it third on my own list, behind a shared number one with Rolling Stone of Richard Pryor's 1978 Live In Concert, and Daniel Kitson's We Are Gathered Here from 2009 in second.

All I have left to write (I'm sure you'll be relieved to know) is this: Thank you, Chris Rock. You may not have meant to change the life and outlook of a white teenager from Birmingham, but you did. May you continue to affect others both like me, and very much unlike me, for many more years to come.

Published: 31 May 2016