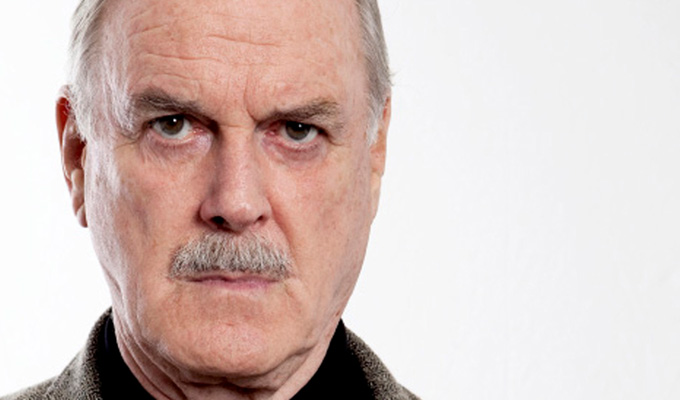

John Cleese

Date of birth: 27-10-1939Cleese was born in Weston-Super-Mare, His father, Reg, an insurance salesman had originally been called Cheese, but changed his surname when he joined the army to avoid being taunted.

John was was privately educated at St. Peter's Preparatory School; Clifton College, Bristol, and Downing College, Cambridge, where he read law and, crucially, joined the Cambridge Footlights, where he met Graham Chapman, with whom he started writing.

Although initially turned down for the troupe, he wrote for their revue in 1961, 1962 and 1963, starring in the latter two productions. It was the 1963 show, A Clump Of Plinths, that gave him and his co-stars their first break; taking the Edinburgh Fringe by storm, then transferring to the West End, Broadway, and a tour of New Zealand under the name Cambridge Circus.

After the New York run, Cleese decided to stay on in the US as an actor, with roles in such stage shows as Half A Sixpence, and trying his hand at journalism, working for Newsweek. While in America he met Terry Gilliam, who was working for a magazine called Help! (he recruited Cleese to appear in a photo-story) as well as a waitress and aspiring actress called Connie Booth, who he would marry in 1968. She gave birth to their only child, Cynthia, in 1971.

Back in Britain, Cleese was given a job as a writer with BBC radio, working on such programmes as The Dick Emery Show, and making the sketch show I’m Sorry I’ll Read That Again with his Cambridge Circus co-stars. The show eventually ran from 1965 to 1974.

In 1965, Cleese and Chapman started writing for David Frost’s The Frost Report, and he also appeared on the programme, including the classic class-based sketch in which he appeared alongside Ronnies Barker and Corbett, each looking up or down on each other. Future Monty Python members Eric Idle, Terry Jones and Michael Palin were also on the illustrious writing team.

Cleese and Chapman also wrote episodes of Doctor In The House, and in 1965 were invited to work with Tim Brooke-Taylor and Marty Feldman on At Last The 1948 Show – the title jokingly referring to the length of time it took the BBC to commission the programme.

In 1969, Cleese and Chapman were offered their own series. But Cleese, reluctant to take the responsibility in the light of alcoholic Chapman’s unreliable behaviour, invited Palin to join them. Since Palin was awaiting an ITV commission with Idle and Jones, they came on board, too, along with Gilliam – and so Monty Python was born as an ensemble piece.

The BBC series ran for four series, from October 1969 to December 1974, but Cleese did not take part in the final run, feeling that the troupe had reached its prime.

However, he was persuaded to return for the film Monty Python and The Holy Grail in 1975, and they subsequently made Life Of Brian and The Meaning Of Life for the big screen, too.

From 1970 to 1973 Cleese served as rector of the University of St Andrews, a role he took surprisingly seriously.

Cleese managed to follow Python with an even more enduring creation, Basil Fawlty, the rude, exasperated hotelier based on a real person, Donald Sinclair. He and Booth, who co-created the series, had been inspired by Sinclair’s bizarre antics running the Gleneagles Hotel in Torquay, where they stayed during location filming on Python – including hiding Idle’s briefcase behind a garden wall, fearing it was a bomb.

The first series began in Septmeber 1975 – but it was four years until the second appeared, due in part to Cleese and Booth’s meticulous planning of each episode. By the time the second series appeared, the couple’s marriage had failed, but they still managed to write together.

He married Barbara Trentham on February 15, 1981. Their daughter Camilla was born in 1984, but they divorced in 1990.

In 1982 he rejoined the Pythons for their Hollywood Bowl show, and masterminded the Amnesty International benefit The Secret Policeman’s Ball, persuading many of comedy’s top stars to take part. Cleese also set up a training company, Video Arts, using his comedy talents in films designed to help workers in their jobs. The company netted him and his three co-founders a total of £42million when it was sold in the late Eighties.

He also has a keen interest in psychotherapy, and has written two books with analyst Robin Skynner: Families And How To Survive Them and Life And How To Survive It.

Outside Python, his Eighties film roles include Time Bandits, Privates On Parade, Yellowbeard, Silverado, Clockwise and Eric The Viking.

In 1988 he wrote and starred in A Fish Called Wanda opposite Jamie Lee Curtis, Kevin Kline and Michael Palin, and was nominated for an Oscar for his script. But the long-awaited follow-up, Fierce Creatures, in 1996 was widely considered a disappointment.

In 1982, Cleese married Alyce Faye Eichelberger, his third blonde American wife, and they remain together to this day, spending most of their time on his Californian ranch.

In the Eighties, he also made party political broadcasts for the Liberal Democrats and the SDP-Liberal Alliance

In 1996, Cleese was offered the CBE, but turned it down.

Cleese’s notable guest appearances include The Muppet Show in 1978; playing Petrucio in a 1980 TV version of The Taming Of The Shrew; playing Q’s assistant in the 1999 James Bond movie The World Is Not Enough and Q himself in Die Another Day three years later.

He has also, lucratively, appeared on some of the most successful US sitcoms in recent years, with a one-off rols in Cheers; and recurring characters in Third Rock Form The Sun (playing Liam Neesam) and Will & Grace, (Lyle Finster).

He is known to a younger generation as Nearly Headless Nick in the Harry Potter films, or possibly as the voice of Princess Fiona's father, King Harold, in Shrek. And he is set to plays Chief Inspector Dreyfus in the 2009 revival of Pink Pather.

Cleese has also leant his voice to George Of The Jungle, Valiant and Charlotte’s Web, the video game Jade Empire, TomTom satellite navigation systems, and Eric Idle’s West End and Broadway Python musical Spamalot, in which he was the voice of God.

In 2005 Cleese toured New Zealand with a live show, but hopes this would spawn more performances around the world appear to have amounted to little, although he did take part in the 2006 Just For Laughs festival in Montreal.

He has both a species of lemur, Avahi cleesi, and an asteroid, 9618 Johncleese, named in his honour.

The archives do not reveal what happened next, but the BBC were apparently successful in seeing off 30-year-old Frost, right, who was already a powerful broadcasting impresario as well as a star. Episode one of Monty Python’s Flying Circus was recorded on September 7, 1969, and premiered on October 5 on BBC One.

The archives do not reveal what happened next, but the BBC were apparently successful in seeing off 30-year-old Frost, right, who was already a powerful broadcasting impresario as well as a star. Episode one of Monty Python’s Flying Circus was recorded on September 7, 1969, and premiered on October 5 on BBC One.