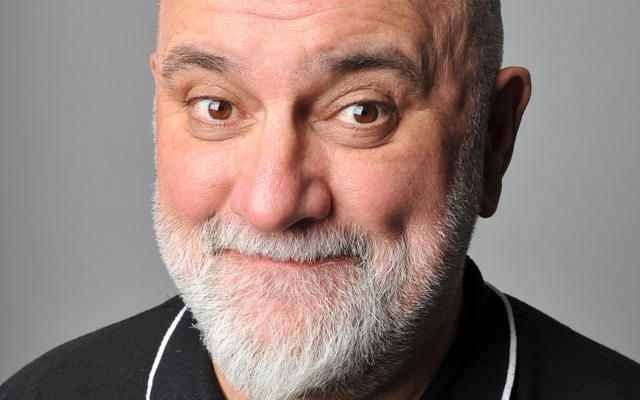

Thatcher Stole My Trousers, by Alexei Sayle

Book review by Steve Bennett

We’ll probably never see anything like the alternative comedy revolution again. Even if the artform detours into another cul-de-sac of tired tropes – where you could argue mainstream stand-up has been heading for a while – the particular economic, social and political forces of the post-punk, nascently Thatcherite era are likely to be unique.

Significantly, the new sort of stand-up seemed to explode from nowhere, while in today’s interconnected age, niches are easier to find. The likes of John Dowie and Ted Chippington, and more visibly Jasper Carrott, Dave Allen and Billy Connolly, laid the groundwork in the 1970s, but it was Tony Allen’s Alternative Comedy and, more importantly, the opening of the Comedy Store that proved a lightning rod for the storms of disenfranchisement that sparked the scene into life, like a destructive Frankenstein’s monster of light entertainment.

Alexei Sayle epitomised that monster: an angry, shouty comedian, verbally attacking the audience with obscure Marxist theory and a violent stream of obscenities. Terror, not the golf-club bonhomie of his predecessors, was his métier – and his brutal manner energised the Comedy Store. As its regular compere, overseeing the gong show brutality from opening night, he was instrumental in making the venue as vital in the transformation of comedy as Peter Cook’s Establishment Club had done a generation before.

Much has been written about this era, but little of it first-hand. And Sayle – one of the few stand-ups to successfully make the transition into a respected writer of fiction – does fine work in combining his own story with the wider ramifications for comedy’s progress.

Thatcher Stole My Trousers picks up from where the first volume of his memoirs, Stalin Ate My Homework, left off. It’s 1971 and he heads for his first term at the bohemian Chelsea School of Art where he was mentored by Anne Rees-Mogg – an unlikely friendship with the wife of the ultra-establishment Times editor William and mother of the throwback arch-Tory MP Jacob.

Meanwhile, thanks to his background with the Trotskyists of Liverpool, Sayle becomes involved in various left-wing factions. He has a finely tuned bullshit detector, though, and makes no bones about the internal squabbles, internecine debates over theoretical doctrine and peculiar characters that have forever led the far-left into the political wilderness

He applies the same unromantic insight to alternative comedy and its exponents, too, pragmatic about its shortcomings as well as its triumphs.

It is around halfway through the book when Sayle gets to planting the seeds of his comedy career beginning his dalliance with Brechtian theatre. That provoked his curiosity about different ways performance, which would go on to inform his stand-up and encouraged him to start working on a sketch show, taking menial part-time jobs from postman to illustrator to pay the rent – the rite-of-passage of every comedian since.

Again the atmosphere of the time was unique, thanks to a quaint old concept called ‘job security’. Sayle writes: ‘My feelings about work had been conditioned by the fact that I had grown up in an era of full employment. If somebody as unreliable and weird as me could walk in and out of jobs, there was no need for me to every worry about getting paid work.’ And so he could focus his full attention elsewhere.

While the received wisdom is that alternative comedy was built on the back of grants, and the welfare state subsidising comedians, Sayle is keen to stress that he also wanted whatever he was offering to be commercially viable, away from the ‘ irrelevance’ of Arts Council-funded projects he saw elsewhere.

For all Sayle’s undoubted contributions to comedy, the unsung hero is his wife Linda, forever offering sage advice. ‘From the moment we met… Linda had seen something unique and original in me, something others didn’t necessarily perceive,’ he writes in one of several passages making the strength of their partnership clear. It was Linda who played the most pivotal role when she spotted a tiny advert in the back of Private Eye in 1979 saying: ‘Comedians wanted for a new comedy and improvisational club opening in W1.’

‘I felt a rush of excitement,’ Sayle writes. ‘This is what I’d been looking for.’ He went to an interview/audition with owners Don Ward and Peter Rosengard at the Gargoyle strip club – and after proving to be the only non-hopeless performer to show up, secured his place in comedy history – even if everyone involved was making it up as they went along.

‘Britain had never had a tradition of smart, anecdotal stand-up comedy so we were trying to build that tradition from scratch while at the same time overlaying it with a left-wing political consciousness,’ he wrote. ‘It’s hard to state how unqualified I was to lead this revolution.’ But – for a while, at least – it worked.

The book contains more than enough great anecdotes from Sayle’s time with the Store, Alternative Cabaret, the Comic Strip and beyond to satisfy anyone interested in comedy history. The night old-school comic Lennie Bennett faced a barrage or derision at the Store, telling the audience as his parting shot: ‘Well, I’m going home in a Rolls-Royce tonight and you’re going home on the bus!’; the awful hotels such as the one where Dawn French and Jennifer Saunders were greeted by an appalling stench later tracked down to a soiled nappy stuffed into a TV set; or the laissez faire approach to health and safety on the set of the Young Ones that sent Rik Mayall to hospital on more than one occasion to name but three.

The book contains more than enough great anecdotes from Sayle’s time with the Store, Alternative Cabaret, the Comic Strip and beyond to satisfy anyone interested in comedy history. The night old-school comic Lennie Bennett faced a barrage or derision at the Store, telling the audience as his parting shot: ‘Well, I’m going home in a Rolls-Royce tonight and you’re going home on the bus!’; the awful hotels such as the one where Dawn French and Jennifer Saunders were greeted by an appalling stench later tracked down to a soiled nappy stuffed into a TV set; or the laissez faire approach to health and safety on the set of the Young Ones that sent Rik Mayall to hospital on more than one occasion to name but three.

There’s some extraneous personal detail about road trips and the like, which does not always contribute to the wider narrative, but Sayle’s straight-talking, witty insight frequently shines, even when talking about himself – admitting, for example, that his favourite type of review is one ‘not only saying I was brilliant but that everybody else was shit’.

And of the culture clash between old-school and new comics, his summary is particularly interesting: ‘I came to the conclusion that mainstream comedians were nasty men pretending to be nice, whereas alternative comedians were nice men pretending to be nasty.’

Though he does have to add the caveat that Keith Allen was the exception…

• Thatcher Stole My Trousers, by Alexei Sayle, was published by Bloomsbury Circus on Thursday, priced £16.99. Buy here

.Published: 13 Mar 2016