I'm a worrier who embarked on the high-risk profession of comedian

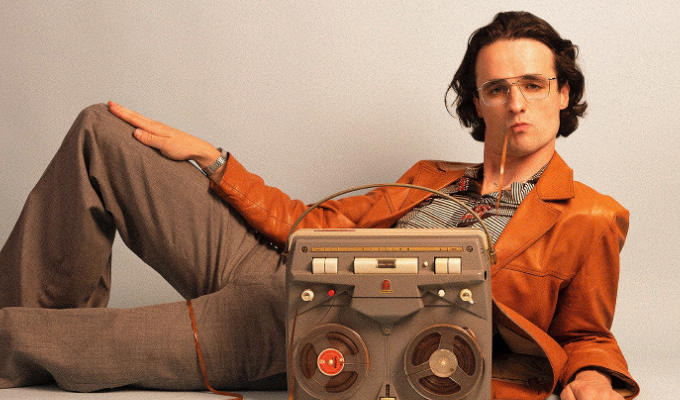

Interview with David Mitchell as he stars in Ludwig

In the new BBC crime series Ludwig, David Mitchell plays John Taylor, a man who lives in quiet solitude designing puzzles for a living, under the nom-de-plume of ‘Ludwig’. But when his identical twin, James, a DCI leading Cambridge’s busy inner-city major crimes team, disappears off the face of the earth, John takes over his identity in a quest to discover his whereabouts.

Here Mitchell talks about the show, the fun of a whodunit, and how the internet has not been good for society…

How did Ludwig first come to you?

The idea was pitched to me quite a while ago. I love TV detective shows. It’s one of the types of programme I find most enjoyable and comforting to watch. I grew up loving Miss Marple and Inspector Morse and Poirot so it’s a bit of a dream for me to be in one.

What appealed to you about the premise of Mark Brotherhood’s script?

It struck me that this was a really fun, funny and different idea. The comedy of a fish out of water but a fish out of water who, if I am going to stretch this metaphor, can nevertheless walk around relatively effectively because of what his previous job in the water was. That’s a great situation.

Also, I like the fact that you get some sort of resolution with Ludwig in one sitting. A lot more television programmes these days are serials. You have to keep watching to kind of get anything. In Ludwig there are rewards for keeping watching every week but equally there is a story in each episode that is resolved, hopefully in a pleasing and intriguing way.

I think fundamentally it’s about the murders and the puzzle solving. I think that’s what is so escapist and satisfying about this genre, the light meringue of a pleasing plot.

Another thing that I like about it is that it’s not gritty. It is cosy murder of the old school. So even though the crime at the centre would be an absolute abomination if it happened in real life, we all benefit from the murder-mystery convention - if you like, the Agatha Christie tradition – so we don’t dwell on what murder really is, on the horrific nature of the crime. We focus on the context and the mystery and the play of human emotions that leads to it.

I have been slightly disappointed, I suppose, by the recent trend of a lot of programmes to really embrace the horror and emphasise the realities of loss and fear that crime causes. That’s not what I’m in it for as a viewer and I don’t think I am alone in that. In Ludwig we don’t dwell on the fact that it’s murder any more than in a game of Cluedo you’d start thinking, ‘But how awful for Doctor Black’s family. He must be so missed.’

Have you always been good at guessing whodunnit in TV murder mysteries?

The truth is I don’t try to guess. I want to be delighted by the denouement. If you have a hard think and you pick someone, you are either going to be wrong - so then you feel like you have been outwitted or that you weren’t given the full information - or you feel like you have robbed yourself of the reveal.

For me, the proof of the pudding is in whether the way the murderer turns out to be whoever it turns out to be is an entertaining revelation. But I know other people like to try and solve it themselves and have little bets and that is an equally valid way of enjoying it.

What sort of man is John ‘Ludwig’ Taylor?

He is a man who has quite a small life. He had a childhood that was massively upset by the disappearance of his and his brother’s father, and John and James for all their similarities have reacted very differently to that. One has headed out into the world, and one has gone into himself a bit.

John has been facilitated in turning in on himself by the fact that he has this great brain for setting puzzles, so he has been able to make a very successful career without much leaving of the house involved.

Broadly speaking he has not aspired to much. He has not taken risks. He has not forged relationships. He has just allowed his brain to comfort him with the setting and the solving of puzzles. He is not a hugely abnormal person. He’s intelligent but he has normal and relatable emotions.

There’s a sadness in him that he hasn’t lived his life to the full and I suppose that is why when a very old friend, his brother’s wife [Lucy, played by Anna Maxwell Martin], comes to him saying, ‘You really have to help us’ he has somewhere got it in him to do that and leave his very, very small, over-heated comfort-zone.

Does John remind you of yourself in your bachelor days?

I’m quite a nervous person, a worrier. At the same time, I am a professional comedian. So ultimately, I did embark upon a high-risk and unusual profession.

Much as I can share the feelings of people like him who don’t want to take risks in their lives and don’t want new experiences, that’s not what I’ve lived. I don’t like extreme sports. I’ve never been skiing. I can’t drive a car. But I will stand on a stage in front of lots of people through choice because ultimately, there is something in me that needs that more than it needs low risks and safety.

What have you enjoyed about your onscreen partnership with Anna Maxwell Martin?

She’s brilliant. I was a big fan of Motherland and I thought she was chilling in Line of Duty. She has a quality of humour and moral ambiguity in her performances that is incredibly watchable. I was delighted when she agreed to do this show because I think she gives a huge slab of acting class to the whole thing. If I can say that. I now feel like I’ve called her a huge slab, which I didn’t mean to do.

John still owns a Nokia mobile phone that Lucy gave him 20 years ago. How are you with tech?

I would say that the advent of the internet and the smartphone has been an unequivocally bad thing for humanity. I think it’s bad for our mental state. It’s bad for our calmness. It’s just bad.

I don’t think that’s because there’s been some grand conspiracy to destroy humanity’s peace of mind. It just happened. That’s the way humans are. We invent things. Technology marches on. Sometimes we invent brilliant things like antibiotics. Sometimes we invent nuclear bombs. I’m afraid I would put the internet in the nuclear bomb camp, not the penicillin camp.

There is a missing conspiracy theorist at the heart of this series. Are there any conspiracy theories that you think are valid?

What I find odd about conspiracy theories is that the people who go in for them invariably like to think of themselves as questioning people because they’ve questioned the ostensible explanation for things that has been presented to them - which is obviously an admirable thing to do - but the trouble is they have questioned explanation number one and then they have taken wacky explanation number two without any questions at all.

I also find it odd that most conspiracy theorists don’t just go in for one conspiracy theory – flat earth or 5G masts cause Covid or Elvis is alive – most of them believe the lot. Why’s that? Just because you reckon the royal family are lizards, why would it follow that you think the planet isn’t a sphere?

I think it’s because going in for a conspiracy theory is a sort of hobby, a state of mind that people enjoy getting into. A bit like watching murder mysteries on television. Unfortunately, with slightly more collateral damage to our society.

What memories were stirred for you returning to Cambridge to film this series?

I had a very happy time at university. It’s a beautiful city and it is lovely to visit. It is always slightly bittersweet because it reminds me that I will never be 21 again. Happy memories of my time there are tinged with regret laced with an awareness of mortality. As we all feel.

Happy memories aren’t just happy, are they? But I also love the fact that it is set in Cambridge. I grew up in Oxford and growing up watching Inspector Morse it felt very special to know the city a bit.

Oxford or Cambridge is a very good context for a programme like this because, in the picturesque and historical surroundings, you can allude to both sides of what the programme needs to be: the attractive, escapist side, but also a sense of darkness and oldness and the fact that humanity is flawed and twisted.

We are told John once found a four-leaf clover but didn’t keep it. Are you superstitious about anything?

I’m afraid I am inclined to habits and worries. I find myself checking that the back door is locked more times than is justifiable. When it has got into my head that something is unlucky, I can’t quite shake it.

I don’t like recurring numbers. In cricket there is a thing that if you are on 111 or any multiple of that, it is supposed to be bad luck. I used to watch quite a lot of cricket so that got into my head and now, if I am reading a book, I won’t leave the bookmark in on page 111. I should, because it is a nonsense not to, but I don’t.

My wife told me that it is bad luck to put new shoes on a table or a bed. Now, if I am ever going on holiday and I am taking new shoes, I pack the suitcase on the floor. So yes, I do accommodate these mad little ideas as part of trying to achieve peace of mind, I suppose. But it is obviously ridiculous.

What’s next for you after Ludwig. Have you any plans to work with Peep Show creators Jesse Armstrong and Sam Bain again?

I would love to work with Jesse and Sam but there are no plans in the pipeline. Sam lives in LA, so I only see him every so often when he comes to visit. Jesse, having been in America for a long time with Succession, is now back here and I am seeing him a bit more often and that’s lovely. My future work plans are that we are doing another series of Would I Lie To You?

- Ludwig starts on BBC One next Wednesday at 9pm, with all episodes on iPlayer. Interview provided by BBC press office.

Published: 19 Sep 2024