© Harry Carr

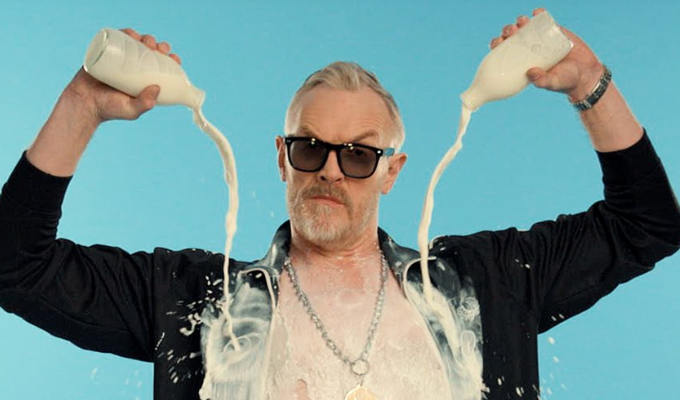

© Harry Carr Simon Amstell: Spirit Hole

Gig review at the London Palladium

Simon Amstell has been on a career-long quest to conquer his hang-ups; to overcome the shackles of shame and embrace spontaneity.

Yet those very same neuroses are the bedrock of his exquisitely crafted comedy. He is the caricature of the fretful, over-thinking Jewish writer, analysing rather than living. Without embarrassment, without an anxious personality that always ‘gets in the way of a good time’, would his stories have such a jagged comic edge?

Thankfully for his audiences, this remains a hypothetical question as he seems to suffer an endless torment of indignities on the quest to live his best life.

This latest bout of soul-scouring was prompted by a trip to New York, which he’d like to portray as a carefree jaunt but knows it’s effectively a midlife crisis: dyeing his hair blond and trying to pull a much younger, muscle-bound barman. However, the encounter only served to magnify his anxieties about growing old in a society that fetishises youth and made him further question why he – and indeed the rest of us – are so deeply in thrall to ego.

In Amstell’s case, that manifests as a nagging inner monologue. He knows by most measures he’s a success, but any joy is haunted by reminders he’s no Timothée Chalamet or Lin-Manuel Miranda – a bar he knows he’s setting too high. It leads to the wonderfully egocentric catchphrase: ‘It’s not relatable, but it’s sad.’

Yet Amstell’s laser-focussed navel-gazing does have a wider resonance as he wittily decodes social niceties or confesses to instinctive thoughts most of us would rather keep hidden. And the fact that almost every nugget of gnomic wisdom is paired with a smart gag makes for a taut, stimulating hour.

He pins down his shame to a lifetime of insecurities about his sexuality, seeded in his teenage years when ‘gay’ was an insult. Now he’s open enough to talk about a trip to a Berlin orgy, or to ask: ’Why all the shame about anal sex?’ – again playing on the intrinsic embarrassment that comes with any talk of intimacy among Brits, let alone this.

Such thinking opens the door for a mockery of toxic machismo. His sketch imagining a marketing campaign for dildos aimed at men is, on the face of it, a straightforward comic set-piece, but enhanced by the social commentary on all the baggage of masculinity, and its damagingly thin definition of how to behave.

Amstell’s escape from such pressures comes via hallucinogens, and Spirit Hole is a veritable advert for mind-altering drugs. Mushrooms give him a vision of his future, irrelevant and invisible, which he actually comes to accept. And he revisits the South American ayahuasca retreat he’s previously spoken about for a particularly dramatic cleansing… where, ironically, he was shamed by the shaman.

The show mixes outrageous stories with insightful thoughts and barbed wit, simultaneously self-lacerating and superior. And since it has a strong thematic skeleton, there’s a satisfying arc, as the vanities and insecurities fade away and Amstell finds himself growing up at the age of 41.

But what is a comedian without ego and angst? We’ll have to wait for the next tour for that. For now, Amstell’s existential crisis and attempts to tackle it are enriching fodder for our entertainment.

Published: 10 Nov 2021