He looked like a flummoxed, cumbersome magician, but every 'mistake' was tightly choreographed

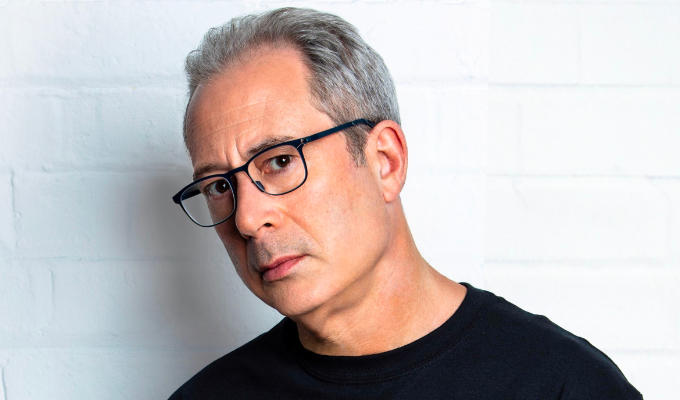

Andre Vincent on the enduring brilliance of Tommy Cooper

‘Spoon, jar. Jar, jar, spoon.’ Transport you back? Or ‘Unfortunately, Rembrandt made lousy violins and Stradivarius was a terrible painter.’ Or the wonderful guest duck clause: ‘But be fair, blindfolded.’

The patter and punchlines of Tommy Cooper were relatively innocuous but his joy of performing always burst through the television screen, filling viewers with pure delight. Cooper’s material may seem unremarkable, his magic tricks imperfect, his persona downtrodden, but he made everything so much greater than the sum of its parts.

Dick Vosburgh - script editor for the 1969 ITV series It’s Tommy Cooper - summed up Cooper’s unique style: ‘Take the joke ‘A man walks into a bar. Ouch, it was an iron bar’. The emphasis should be on the word iron. Not Tommy, he would stress the word bar. The way he says it is all wrong, but it doesn’t matter with Tommy, he’s funny. In fact, doing it that way, in his hands, somehow makes it more funny.’

Cooper delights in his own jokes; you could see in his eyes he had something marvellous to share, like a child who is thrilled by what they have brought to class. This pre-emptive, innocent excitement prepares the audience who then enjoy the delivery all the more.

Cooper could get away with a lot in pursuit of a laugh. During the age of variety, Cissie Williams was the stern chief booker at Moss Empires, known for castigating anyone on her bills who stepped out of line. She famously sacked Frank Randall for calling an audience member a bastard when he threw things at the comic during a performance at Finsbury Park Empire. The other acts defended Randall but Williams was unmoved. It therefore shocked the entertainment world when Cooper told a notoriously Anglophobic crowd at the Glasgow Empire to ‘all fuck off’, that Williams’ reaction was: ‘Great, it’s about time someone told those bastards to fuck off.’ Performers everywhere shrugged their shoulders and sighed: ‘Ah, typical Tommy.’

Thomas Frederick Cooper was born on March 19, 1921, in Caerphilly, South Wales but the family relocated to Haven Banks next to the River Exe in Exeter when he was three. Cooper attended Mount Radford School for Boys, and at weekends helped out in his parents’ ice cream van.

At the age of eight, Cooper’s Aunty Lucy gave her young nephew a magic set for Christmas and he spent hours perfecting its tricks. In 1933 the family moved to Southampton where, two years later, the 14 year-old Tommy left school to become an apprentice shipwright at the British Power Boat Company based in Hythe Docks.

It was there that Cooper made his first attempts at performance. After trying out magic tricks on all the other staff, it was suggested that he did a spot at the works’ Christmas show. When his big moment came, he was shaking with nerves. Everything went wrong, even his big finish in which he upturned a bottle of milk. As he recalls it: ‘The stage was swimming with milk. I dropped my wand. I did everything wrong. But the audience loved it, the more I panicked and made a mess of everything, the more they laughed. I came off and cried, but five minutes later I could still hear the sound of laughter in my ears and was thinking - maybe there’s a living to be made here.’

With the outbreak of the Second World War, Cooper joined the Royal Horse Guards and was stationed as one of Monty’s Desert Rats in Egypt. Still wanting to entertain, he volunteered for the Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes where he learned to perform sketches and song and dance routines, while also working on his solo act.

The book Fighting for a Laugh which focuses on wartime entertainers describes Cooper as ‘a bastard to be with as an officer, because he delighted in getting you up on the stage to help him out and then he would take the mickey out of you something terrible. He had the whole of the audience on his side and if you weren’t careful, you came out of it looking none too dignified’.

It was during his time in Egypt that Cooper established his most important prop: the fringed red fez. During a sketch, he discovered that his pith-helmet had gone missing so he grabbed a passing waiter’s fez as a substitute. It seemed to increase the laughs, and from that moment the hat became Cooper’s trademark. Already 6ft 4in tall, Cooper gained another eight inches when he wore the fez, making him a towering stage presence.

It also brought him closer to two of his greatest idols, Laurel and Hardy, who wore fezzes in the film Fraternity Yours. Cooper was fascinated by showbusiness and loved to work with performers he admired. A big fan of Arthur Askey, Cooper made a beeline for pantomime parts alongside his idol. His early career also saw him on the same bill as Max Miller whose influence is evident in Cooper’s rhythm - no excess words, straight to the punchline, then on with the next joke: pure Miller.

After the war, many of the NAAFI comedians Cooper had worked with moved into broadcasting but radio was not a suitable medium for a prop magician. Instead, Cooper worked the variety clubs and halls of Britain, often at the foot of the bill. He pushed his act, constantly changing the format, the props and the jokes. When Bob Monkhouse recalled working with Cooper in revue, he described him walking out on stage each night to bring something new to the audience. Cooper would shout: ‘Watch, watch, watch!’ and then produce a big watch. The following night he would say: ‘Ladies and Gentlemen, my big opener’ and then pull out a large tin opener.

Cooper found representation from the agent Miff Ferrie, a one-time trombonist with the band The Jackdaws. Ferrie regarded himself as a comedy expert, even if the creator of The Rise and Fall of Reginald Perrin, David Nobbs, claimed Ferrie to be ‘about as funny as Liverpool Street station’.

Ferrie secured work for Cooper immediately and the years 1948-49 were hectic: a major tour of Europe, a summer season, a pantomime and a long run at the legendary Windmill Theatre, plus extra cabaret and revue spots wherever he could get them. It was reported that in one week during that period, Tommy Cooper performed 52 shows.

His reputation as a first-class entertainer soon came to the attention of BBC television. In 1952, producer Graham Muir made Cooper the host of It’s Magic. Cooper’s madcap ways didn’t fit in with a traditional magic show, so it was eventually handed over to David Nixon who presented it for the following five seasons. Finding a vehicle for Cooper proved difficult. He appeared as a guest on countless shows and would usually steal every laugh and accolade. It became known that an internal row was brewing between Billy Cotton Jr, head of variety, and Frank Muir, head of comedy, over who should create a show for Cooper.

Miff Ferrie cleverly leveraged this squabble to broker a lucrative deal at ABC Television. The resulting production based at Teddington Studios was Cooper (or Life with Tommy). The show was too fragmented to work, but ABC stuck with him. The Tommy Cooper Hour followed - a one-off special in which his entire stage set was filmed; then Cooper’s Capers, a sketch show imagining Cooper bumbling through his daily routines. Neither found the right balance. Cooper himself genuinely didn’t care. He was still enjoying being on the road and performing live, with the occasional TV special including The Ed Sullivan Show in the US, plus film appearances in And The Same To You and The Cool Mikado.

In the 1960s, Cooper was at the top of his game. He was working hard and making money to support his wife Gwen and their children, Tommy Jr and Victoria. The family were relatively comfortable: a large house in Chiswick, a second property in Eastbourne, and regular holidays abroad, but Cooper’s reputation in the industry was as a penny-pincher.

He loved to buy new comedy props and magic equipment, trawling the magic shops of London to find the latest gadgets. One of Cooper’s favourite shops was Davenports, then across the road from the British Museum. As he entered the shop he was often heard to say: ‘I get me props in here - and me jokes over there,’ indicating the opposite building.

Cooper’s comic sensibility was never turned to off, and his impromptu clowning made for some sparkling anecdotes. Stopped by the police for speeding, his reply to the officer’s apologetic ‘Sorry sir, I’m going to have to book you’ was ‘You’d better go through my agent’ Seated on a London Tube train, Cooper watched a vagrant haul his mongrel through the carriages while shouting ‘I’m hungry.’ Without missing a beat, Cooper suggested ‘Well, eat your dog’, causing hysterics among the other passengers.

Few comedians had Cooper’s charisma in a crowd. Eric Morecambe once told a group of reporters gathered around him after a show: ‘You’re listening to me now but if Tommy came in, everybody would go [to him].’

On June 18, 1966, ABC broadcast Cooperama for ITV. This time the format worked; a mixture of sketches, monologues and magic. The production team found the right people for Cooper to work with - directors, comedy writers and script editors who were all tuned into his idiosyncratic humour. In two years, Cooper recorded more than 45 shows for ITV, including a one-hour special, broadcast on the opening night of the new Thames TV. Sadly, the audience at home only saw 20 minutes as the station was subject to industrial action.

Also in this decade, Cooper became member no. 595 of the charitable Grand Order of Water Rats. He was very proud to join the fraternity and to represent them in performances at charity events, balls and Royal Command shows. Cooper can be seen wearing his Water Rats emblem many times on TV, affording the brotherhood due dignity. That, or he didn’t want to run up Water Rats fines for being seen without it. At celebrity luncheons, Cooper was the perfect guest, guaranteeing big laughs and bare-faced cheek. At a lunch attended by Dean Martin, Cooper declared: ‘It would have been great if Jerry Lewis had been here, along with that one he works with, that Italian.’ Everyone in the room roared with laughter, including Dean Martin, who had only just met him.

In 1967, Cooper began an affair with his personal assistant, Mary Fieldhouse, which would last for much of his life. The stress of maintaining two relationships and a working schedule packed with live and TV appearances led him increasingly to alcohol, and stories of Cooper’s intoxication, unprofessionalism, tardiness and tendency to walk off stage after five minutes began to spread. Bookers seemed to accept this as part of the Tommy Cooper package. When he turned up late for a show and was greeted in the car park by a frazzled concert secretary who remarked: ‘You were on 30 minutes ago!’ Cooper said: ‘How did I do?’.

By the beginning of the 1970s, Cooper’s health began to decline. Perpetual heavy smoking and drinking increased his suffering from chronic indigestion, lumbago, sciatica, bronchitis and severe circulation problems in his legs, but he still refused to ease up on his heavy workload. The more he worked, the more he drank. The more he drank, the more sick he became.

When filming a commercial for SodaStream, he was so unwell that his voice had to be dubbed with that of a Cooper impersonator. Even his car insurance company was aware of this excessive drinking. His cover renewal arrived one morning with a customised exclusion clause referring to ‘a state of intoxication or whilst suffering from alcoholism directly or indirectly’.

In 1977, Cooper’s ill-health reached a crisis point. Performing at a corporate gig in Rome, he suffered a heart attack. This should have been a wake-up call to slow down and stop drinking but he was back on TV just three months later.

It took three more series with Thames TV for them to realise that Cooper wouldn’t – couldn’t – stop drinking, and in 1980 his rolling contract was not renewed. His last show for Thames was a reprisal of his character from the hit short film The Plank, broadcast as the one-off special It’s Your Move in 1982.

On April 15, 1984, Cooper performed on the London Weekend Television variety show Live from Her Majesty's. At the point of his final trick, an assistant helped him put on a cloak from which props would appear after having been passed to him through the back curtain. The assistant laughed as she left the stage because Cooper slumped and started sliding down the curtain. Just like the audience, she thought it was part of the act.

After Cooper hit the ground, Alasdair McMillan, the show’s director, cued the orchestra to play, and the channel cut to an unplanned ad break. Cooper had suffered a massive heart attack in front of a live auditorium and over a million TV viewers. How else would you expect him to go?

Cooper’s death rocked the nation. An outpouring of grief sprang from fans of all ages; an auction of his props in the late eighties drew both Norman Wisdom and Ade Edmondson as bidders. In the Reader’s Digest 2004 vote to find the Funniest Briton Of All Time, Tommy Cooper topped the poll, with Peter Kay in second place.

Cooper’s work was almost exclusively apolitical, non-sexist, non-racist and non-homophobic. He would have fitted comfortably into the alternative/New Wave scene that was just developing when he passed. Always true to himself and what made him laugh rather than the comedic zeitgeist, Cooper’s simple style dates well and his influence is extensive: Tim Vine, Otiz Cannelloni and Stewart Francis could be seen to follow in his tradition.

It’s been 40 forty years since Tommy Cooper died and yet he remains many people’s favourite comedian. Nearly every Christmas, a TV channel will create a new show celebrating his artistry, or a show in which an impersonator recreates Cooper’s routines as an homage to his genius.

There is a statue of Cooper in Caerphilly and a blue plaque at his family home in Chiswick. This gentle giant excelled in fabricating the appearance of a flummoxed, cumbersome magician, desperate just to keep the act going, when in fact most of his ‘mistakes’ were tightly choreographed. Cooper’s apparent mishaps had audiences beside themselves with laughter, and he liked it like that, just like that.

• Andre Vincent is a comedian and comedy historian, whose own website Mislaid Comedy Heroes celebrates the best of Britain's comedy heritage.

Published: 19 Mar 2021