All their yesterdays...

20 years of Blackadder

It looked like becoming one of the most expensive mistakes in the BBC's history. The corporation had spent an unprecedented £1million on a new sitcom - a huge amount of money in 1983 - and was expecting great things. Yet their attempt to harness the talent of an emerging generation of bright new comedians had turned into a huge disappointment, producing a messy, frequently unfunny, shambles in which the actors - and the jokes - were dwarfed by the ambitious scale of the sprawling historical production.So when the first episode of The Black Adder was broadcast after the Nine O'Clock News on a quiet Wednesday night 20 years ago, no one could have imagined it would come to earn itself a cherished place in Britain's comic treasury. And certainly not the BBC executives who vowed never to make the mistake of commissioning a second series.

When the idea was first mooted, it seemed like a sure-fire hit. Not The Nine O'Clock News was one of BBC2's biggest hits of the time, and combining the talents of its most promising star, Rowan Atkinson, writer, Richard Curtis, and producer John Lloyd should have been a winner.

They had the big idea, too. They wanted to set their sitcom in the past.

This was by no means a new thought; it had already been famously embraced by Frankie Howerd in Up Pompeii!, itself inspired by the 1966 movie A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum.

But Atkinson, Curtis and Lloyd took their cue from such Hollywood swashbucklers as Errol Flynn's Robin Hood, and set their show in the Middle Ages, and seeking to recreate an authentic period feel. Rather than using camp asides, modern sensibilities and cheap anachronistic gags to get their laughs, they would stay true to the spirit of the age.

However, there was another, more pragmatic, reason for their decision.

"Richard and I both felt the scourge of Fawlty Towers, the dominant sitcom of the time, hanging over our heads as something to which we would be unfavourably compared," Atkinson reveals in a new Radio 4 interview to celebrate two decades of Blackadder. "And that is one of the main reasons why we thought of doing a period sitcom."

Setting the comedy in late medieval times had other advantages. It was a time when life was nasty, brutish and short; the threat of extreme suffering or death gave the comic set-ups an extra edge. If comedy is tragedy plus time, as the old saying goes, 500 years should be long enough.

The premise was that history had literally been rewritten to eradicate all trace of a troublesome branch of the Royal family - but one slow-witted heir survived: Edmund, Duke Of Edinburgh - the self-styled 'Black Adder'.

A pilot episode was made in 1982 - a show that has never been broadcast, though reportedly bears strong similarities to the TV series. The main exception that the role of sidekick Baldrick was played by actor Philip Fox, rather than Tony Robinson.

It was enough to convince the BBC to make a full series of six 35-minute episodes, recruiting established stars Brian Blessed and Peter Cook as well as using up-and-coming comics like Angus Deayton and Rik Mayall for bit parts.

The show was expensive to make. The traditional studio-based sitcom setting had been abandoned for location filming in Alnwick Castle, Northumbria. Additional dialogue, the credits claimed, was by William Shakespeare.

"It was very extravagant, very expensive," Atkinson says today. "The joke was that it looked a million dollars, but cost a million pounds. It looked great, but it wasn't as consistently funny as we wanted it to be."

Robinson is more direct. "We all knew from the beginning the first series was pretty dire," he says. "And at the end of the series everyone said at the BBC, 'Well it didn't really work, did it? We won't be giving you another one.'"

That BBC1 controller Michael Grade reluctantly relented was down to one event - The Black Adder winning a prestigious International Emmy award in the US. He may have thought the show was an expensive mistake, but the praise of their peers was enough - just - to prompt a change of mind.

For the second series, the action was shunted forward a century to Elizabethan times - partly out of necessity as all the original characters had been killed off at the end of the first series. Ben Elton was drafted in as a co-writer, leaving Atkinson to concentrate solely on his role - one that differed substantially from the original.

"In series one, we bit of slightly more than we could chew," says Curtis, who has since found fame, and fortune, as the screenwriter of Four Weddings And A Funeral and Notting Hill. "With Rowan's character, we tried to make him arrogant, scared, feeble, bullying. It was too much for one character to hold. In series two, and made him simpler."

Atkinson agrees, telling Radio 4's I Have A Cunning Plan: "They decided, rather bravely I thought, to make the central character less silly, less comic, less daft and make him rather cool and sardonic and cynical."

Another change was to dumb down Baldrick and Lord Percy further still. "In the first series, Baldrick was by far the smartest," Robinson says. "But Blackadder needed, in his own world, to be brilliant... so you needed real thickies as his sidekicks."

Combined with Miranda Richardson's extravagantly childish, over-indulged Elizabeth I and Stephen Fry's ineffectual Melchett, the show proved a runaway success - even if creating it was dogged with difficulties.

"It was not necessarily a consistently happy time," Atkinson says. "Creatively it was quite fraught. With the these distinct comic energies between the writers, producers and actors - a lot of whom were writers in their own right - it was bound to lead to rows about the material and the jokes we were trying to get across."

"None of us ever knew our lines because we didn't do any rehearsing," Robinson agrees. "All we did was argue about the script all week long."

The new-found success led to the third series, set in Regency times, a number of charity specials, and the acclaimed Blackadder Goes Forth, set in the trenches of the First World War and culminating in that unforgettably poignant closing scene.

"It was a fantastic place to set something," Curtis says. "All the classes meeting in a tiny, confined room - the trenches - ideal for a sitcom, but a very tragic thing."

"We didn't aim to make the ending moving," Elton adds. "But we did aim to make it sincere."

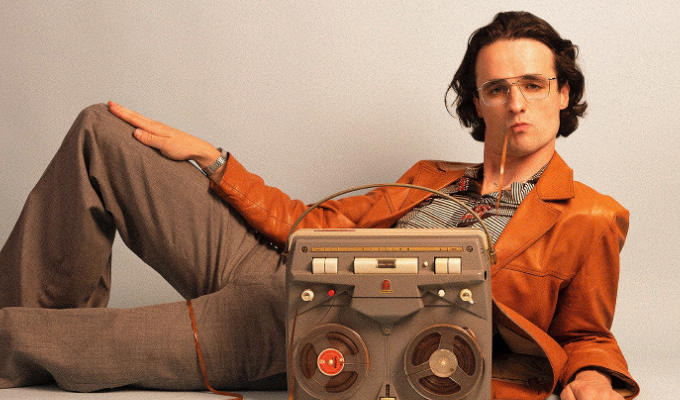

Plans were mooted for a fifth series, the most likely setting being a Sixties pop band called the Blackadder Five, with Atkinson playing a manipulative svengali and Robinson the group's folically-challenged drummer, Bald Rick. But nothing came of this, and with all the key players pursuing their own successful careers, a major reunion is increasingly unlikely.

Yet the team have nothing more to prove. They produced one of the all-time great British sitcoms which, perhaps because of the attention to historical detail, has remained remarkably undated over the past two decades.

Curtis says: "While we were doing it, I remember saying to Ben, 'It's good, but it will never be great.'". How wrong he was.

First published:May 25, 2003

Published: 22 Mar 2009