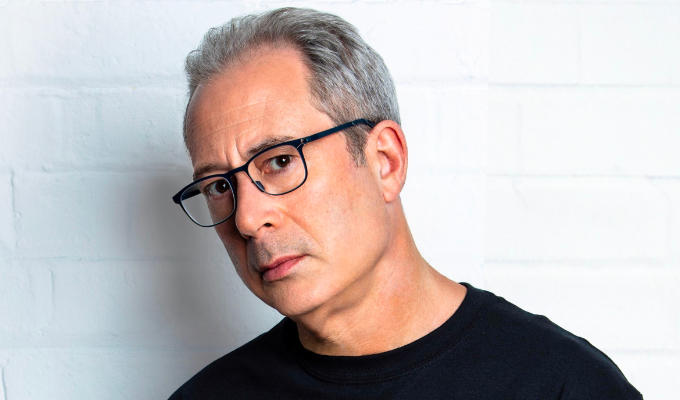

Stewart Lee's comedy has no future

Joe Daniels considers a stand-up hero

Stewart Lee is widely considered the best comedian working today, and while this claim is swiftly dispatched by his detractors, it is precisely this divisiveness that reinforces his status. Some people hate him, and therefore the initiated love him even more.

This is the line many take when speaking in praise and defence of Lee’s longwinded, formless style, his dry, laconic prose-poetry. It is also well noted that his repetitive delivery, so steeped in irony, is his calling card, and he is able to make long-winded routines about wishing harm on Top Gear presenters funny because of his linguistic nous and reflective self-awareness. Irony, it is said, is his strength. And whilst I daren’t dispute any of this, I do rebuff the oft-banded claim that he represents ‘the future of comedy’. Its much more plausible to me that he rather represents a deadpan dead end in comedy.

Here I run the risk of coming over a bit sensationalist, though this is not my intention, and even if it were, I’d be no more melodramatic in decreeing Lee a Cul-De-Sac in comedy as the dozens who decree him its lifeblood. What is needed here is an understanding as to why we should consider him at some place in the history of comedy at all. Why bestow such significance not only on his work, but his potential legacy?

The answer is, of course, because of the traits that have made him a name, specifically his penchant for marring form and content. His self-referential shtick, dripping with that aforementioned irony, is both an attempt to refine an audience, and to extrapolate his own perceived image. He seeks to take his performance to its own conclusions, but outside of its own form. It’s unsurprising that he champions musicians John Cage, Derek Bailey, and Mark E. Smith given their shared affinity for raucous, raw performance, unrestrained by the trappings of considered form.

We often see him play out imaginary conversations with himself, acting as a choric commentary on what he’s doing, or thrashing around the boxes of some Victorian theatre while lambasting other comedians. It’s an image that resonates with his three idols: all aging, under-appreciated avant-gardesters desperately trying to prove they’re better than their audience can ever know.

Lee’s brand of humour is a distinct meta-humour. It is comedy about comedy, writing about writing. The New Yorker magazine has been doing something similar for the last 80 years, satirising their own endeavours as they go, and the result over there is the same: a transformation of audience. The New Yorker’s readers became atoned to the smarmy, dandyish posturing of the magazine’s humour, and adapted to it; the letters to the editor become more irreverent, and its subscribers more eccentric.

What we have with Lee, though, is an overt attempt at refinement, the result of an audience gained primarily through television. Lee builds his humour on an apparent discrepancy between the intellect of his actual audience and the intellect of the one he believes he deserves. Of course, this is silly, self-aware posturing.

He, like Kitson, operates behind the veil of showbiz that is itself ridiculous. They are performing heartfelt, honest productions of their own creative making, but they are still performing. They have an audience before them that they must entertain (in some sense of the word), and whilst they may be uncomfortable with the corporate trappings of industry, in the end, it is still the audience they must answer to.

The difference between these auteurs and the hackneyed stuff we all whine about on these forums is precisely this awareness, this meta-performance. Lee’s unique status as comedian’s comedian, able to disparage his peers without the impunity typical of comedy’s fraternal watchdoggery, has earned him a honed audience of devotees, committed to his sarcasm-soaked iconoclasm. But because of the complex relationship between artificer and art that exists in stand-up, particularly so with a stand-up as introspective as Lee, it becomes hard for an audience to distinguish where the performance ends and he begins. So steeped in his own propagated image, Stew exists as an abstraction, a warped cipher.

Fittingly, it seems ironic that the finale of the second series of Stewart Lee’s Comedy Vehicle focused so heavily on criticising the inherent elitism of the Tories, given that his act is one reliant on a specific brand of cultural hierarchy. The enjoyment of Lee’s act is conditional on the audience running with his muddied elitism, oscillating between various types of snobbery (he hates in equal measure: the media-saturated young, the politically incorrect elderly, the dunce half of the room that doesn’t get it, and the boffin half that does).

Here then lies the rub. For Lee’s act to work, there needs to be an assumption that dichotomies exist; that there is a high to which everything should aspire, and a low to which it can plummet.

But, all the while, it is understood that these are false dichotomies that only really exist for the sake of his comedy. Take, for example, the fact that the celebrities he goes after, such as Adrian Chiles, Russell Howard, and ‘Paddy Thing’ are pretty innocuous public figures. It is not what they have done that makes them Lee’s prey, but what they haven’t. They are not boundary pushing provocateurs; they are simply honest celebrities, doing the honest celebrity thing.

Likewise, they are not monstrous criminals. It’s funny because they are not the easy targets, neither are they particularly difficult, they are just recognised. It’s comedy based on the shared assumption that for the duration of the set, popular culture has to fall under Lee’s dogmatic system of juxtaposition.

For all the postmodernist playfulness and elitist bluster, Stewart Lee relies on the established conventions and characters of comedy in order to subvert them. His act only works when enough people out there like seeing Michael McIntyre bound about in enormo-domes, for in Lee’s utopian society, there’d be no one to scoff at. The grumpy persona he purports sleeps on a bed of comfortable popular taste. In all its bubblegum chintz, popular culture is the essence of Stewart Lee’s act: it’s the Other with which he must reconcile or revile.

To conclude, then, this is comedy in a vacuum. It can go nowhere as it exists only to deconstruct itself. Allied to this actuality is the fact that this alternative, genre-defying performance has to exist one step behind the mainstream, and not one ahead. It is reactionary in its truest form, and whilst I do not deny how wonderfully funny and intellectually stimulating it is, I cannot see any future in it. Sorry, Stew.

Published: 5 Jul 2011