42: The Wildly Improbable Ideas of Douglas Adams

Book review by Steve Bennett

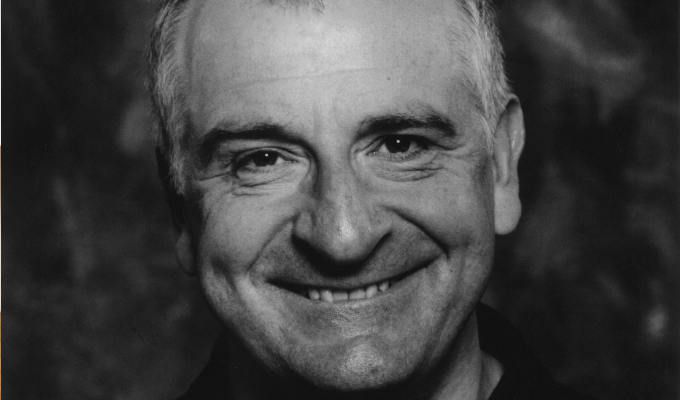

After Hitchhikers Guide To The Galaxy author Douglas Adams died in 2001 at the unfairly young age of 49, his family donated 67 boxes of his archives – notebooks, letters, scripts and speeches – to his old Cambridge college, St John’s.

From that treasure trove, documentary-maker and Adams fan Kevin Jon Davies has extracted this fascinating and lavishly presented collection of material that throws new light on the ever-inventive comic genius.

It starts with Brentwood School reports, including his Upper II English teacher summing up his entire year’s work as ‘quite good’ – almost as dismissive as ‘mostly harmless’, Ford Prefect’s two-word description of Earth after 15 years’ research for the Guide – and his Upper Sixth art teacher praising his ‘admirable’ ideas but dismissing him as a ‘dilettante’.

And it ends with an address Adams gave to a tech conference months before his death about his plans for a collaborative online encyclopaedia, H2G2, which was soon to be eclipsed by Wikipedia.

At school, Adams dabbled in debating and homemade magazines that showed early promise (his review of Oliver Twist? ‘Unsuitable for those with a social conscience in a starving world; glutton makes good’), before joining the Cambridge Footlights at university, where he worked on revues with the likes of Clive Anderson and Griff Rhys-Jones.

His first gag to be broadcast to the nation came just before he graduated in 1974, when a sketch about Richard Nixon and Watergate was chosen for Radio 4’s open-access topical comedy show Weekending. The most prescient comment comes in a notebook entry from about the same time, in which he wrote: ‘Science fiction story: Man goes to friend; reveals that he is in fact an alien (they have known each other many years), he must now leave the Earth, which is threatened with extinction and offers to take his friend with him.’

It would take four years for that notion to make it to radio as the first incarnation of the Hitchhikers Guide. In the meantime, he formed a not especially productive friendship with Graham Chapman, worked on radio shows such as The Burkiss Way and tried to write for Doctor Who. An idea he submitted in 1976 was rejected with a brutal dismissal, kept in this archive: ‘We do need greater evidence than this of real talent.’

Around this time, he suffered a crisis of confidence and applied for a job with P&O in Hong Kong, it is revealed. His letter told them: ‘I’ve come to feel that, working in television entertainment is 95 per cent a useless and trivial activity, and since I am (I hope) intelligent, educated and ambitious, it’s time I turned to something more productive… I would like to be involved in the job of generating wealth.’

He did eventually work on Doctor Who and get Hitchhikers commissioned (Arthur Dent’s original name was Aleric B, we see from the notes), although writer’s block – or sometimes an even more gnawing disillusionment with what he was doing – seems an occasional occupational hazard. One of his most famous quotes is, of course: ‘I love deadlines. I love the whooshing noise they make as they go by.’

In a ‘general note to myself’ reproduced here and which may benefit anyone struggling with creativity, he said: ‘Writing isn’t so bad when you get through the worry. Forget about the worry, just press on. Don’t be embarrassed about the bad bits. Don’t strain at them. Give yourself time, you can come back and do it again in the light of what you discover about the story later on. It’s better to have pages and pages of material to work with and maybe find an unexpected shape in that you can then craft and put to good use, rather than one manically reworked paragraph or sentence.’

The lost ideas are, of course, much of the fun of this book. For example, Adams wanted the stars of the TV adaptation of Hitchhikers Guide to be always accompanied by a goat with a scale model of the Eiffel Tower in its head, which they would never mention. A budget-conscious producer decided this result of the Infinite Improbability Drive was not a joke worth keeping.

The book includes all sorts of random details: previously unseen designs for a ride at Chessington World of Adventures; his student union card endorsed by future Foreign Secretary Jack Straw; his reflections on book signings and Concorde’s decor; plans to make the Meaning Of Liff – the book of odd definitions he wrote with John Lloyd – into a TV series fronted by Rowan Atkinson.

Given the ephemeral nature of such content, and Davies’s decision to largely let it speak for itself, with only the minimal of commentary or context, the picture that emerges of Adams is incomplete. But he’s such a fascinating figure that even these piecemeal insights into his creativity are a delight. What shines through is Adams’ off-kilter wit in almost everything he wrote, even stock responses to fan mail or

His varied passions are reflected as the book moves through later periods of his career – Dirk Gently, his conservationism and the Starship Titanic video game – as well as his burgeoning interest in technology, especially Apple products.

Now nothing is handwritten or typed on paper – a development Adams would have surely embraced – archives like this, full of crossing outs and hastily scribbled edits, will be a thing of the past. We might not see a book like this again. And we certainly won’t see a mind like Adams’s again.

• 42: The Wildly Improbable Ideas of Douglas Adams has jumped straight to No 1 in the Sunday Times general hardbacks chart – the first such achievement for any book from crowdfunding publisher Unbound. It is available from bookshop.org, below, aiding independent retailers, or from Amazon, priced £24.99.

Published: 5 Sep 2023